["f3af8dbe37a29fdc17156180c690ea44580a9437"]

Gynecomastia

gynecomastia

pseudogynecomastia

lipomastia

5395

5395

Chapter reads

2

2

Chapter likes

7/10

Evidence score

11

11

Images included

04

4

Videos included

01

Introduction

Introduction

Gynecomastia means unilateral or bilateral benign enlargement of the male breast. It can lead to female appearance and consecutively to severe strain of those affected.

The true gynecomastia with actual hypertrophy of glandular tissue is differentiated from the so-called pseudogynecomastia with mainly fatty tissue growth typically associated with adiposity.

Both types can result in considerable psychological stress and disturbance of the self-confidence. A retrospective single center analyses of 35 patients revealed that gynecomastia in adolescents presents a psychological threat to normal self-esteem as well as sexual identity1.

Hence, gynecomastia represents a serious disorder that needs to be treated appropriately.

The true gynecomastia with actual hypertrophy of glandular tissue is differentiated from the so-called pseudogynecomastia with mainly fatty tissue growth typically associated with adiposity.

Both types can result in considerable psychological stress and disturbance of the self-confidence. A retrospective single center analyses of 35 patients revealed that gynecomastia in adolescents presents a psychological threat to normal self-esteem as well as sexual identity1.

Hence, gynecomastia represents a serious disorder that needs to be treated appropriately.

02

Anatomy of the male breast

Anatomy of the male breast

Anatomy male breast

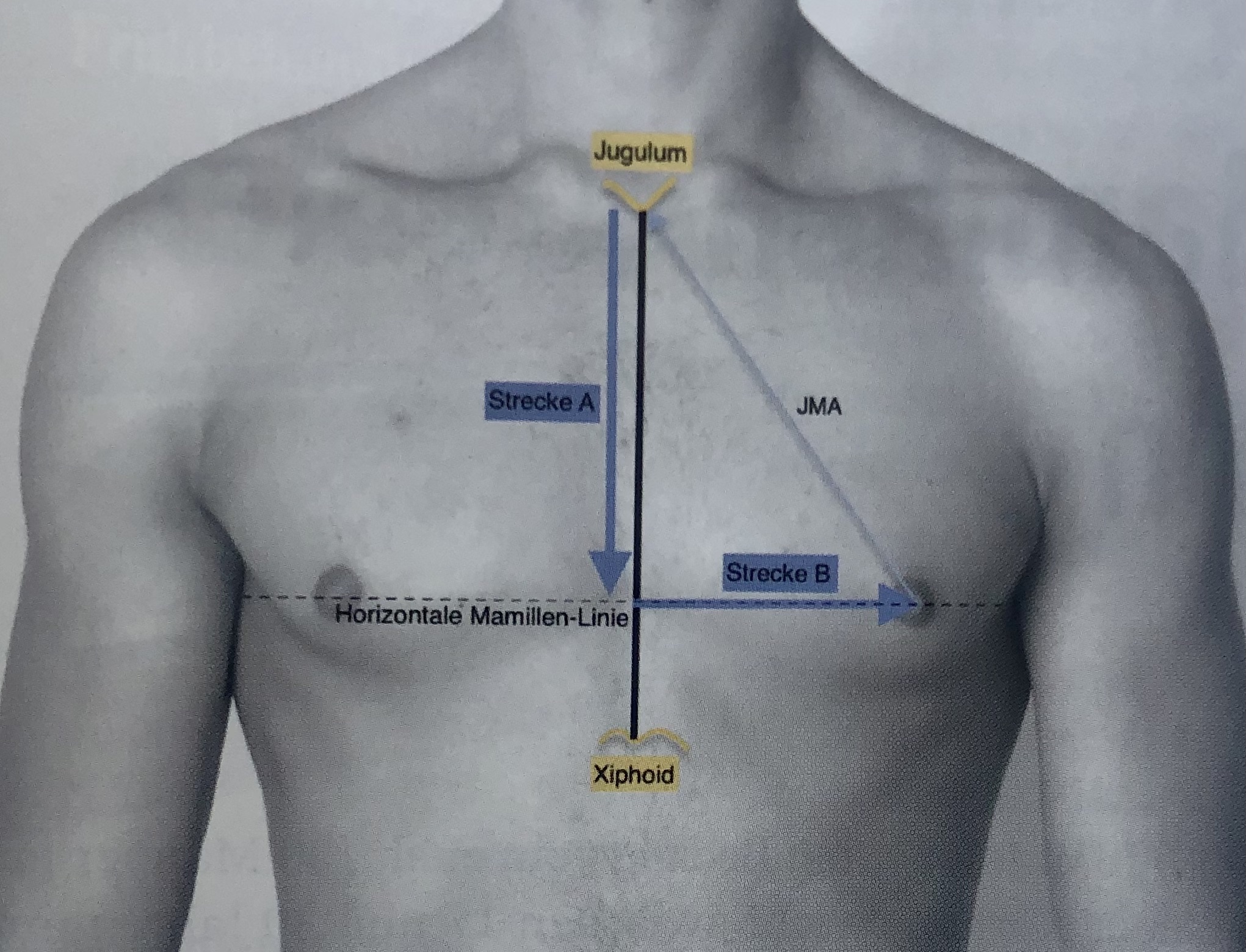

Topography of the ideal male breast

Flat shape accentuating the pectoralis major muscle

Extends from the 2nd to 6th anterior rib

Medial border: sternum

Lateral border: mid-axillary line

NAC (nipple areola complex):

smaller compared to female and slightly oval (average NAC diameter: 26 x 20 mm) [2-4]

slightly cephalad to the caudal border of the pectoralis major muscle [2, 5]

intercostal space between 4th and 5th rib [4-6]

the ideal NAC position is rather depending on BMI and different body shapes than on average body measurements [7] – e.g. with increasing BMI the NAC is located more lateral [8, 9].

--> Respecting the thorax circumference the algorithm of Beer et al. [2] seems most reasonable for the calculation of the idela NAC position:

--> Respecting the thorax circumference the algorithm of Beer et al. [2] seems most reasonable for the calculation of the idela NAC position:

Ideal position of the male nipple-areola complex.- Modified from Beer et. al., by Given et al. Plastische Chirurgie, 16. Jahrgang Heft 2/2016

Distance A = 1.2 + (.28 x length of sternum) + (0.1 x thorax circumference) [cm]

Distance B = 2.4 + (0.09 x thorax circumference) [cm]

modified from Beet et al. - PRS 2001 Dec;108(7):1947-52; discussion 1953. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200112000-00015. [2]

Distance B = 2.4 + (0.09 x thorax circumference) [cm]

modified from Beet et al. - PRS 2001 Dec;108(7):1947-52; discussion 1953. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200112000-00015. [2]

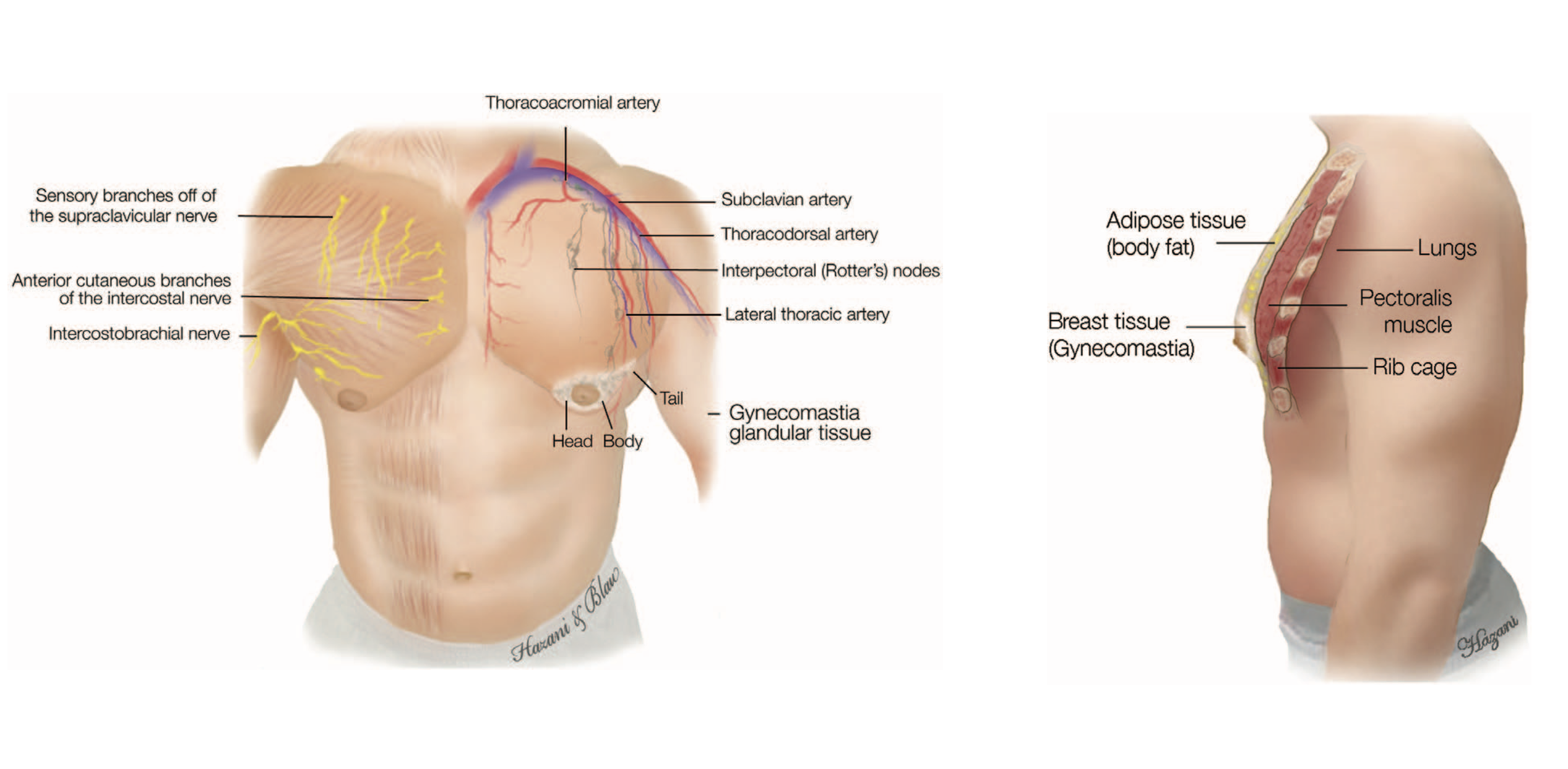

Vascular supply

Arterial and venous supply follow the same pattern. Breast parenchyma and skin are supplied by:

perforating branches of internal mammary artery

lateral thoracic artery

thoracodorsal artery

intercostal perforators

Textthoracoacromial artery

Innervation

Breast innervation is provided by the supraclavicular nerves and by the lateral and median branches of the intercostal nerves - similar to the female breast:

The supraclavicular nerves are said to innervate the upper part of the breast excluding the gland [10]

Branches of the 6th intercostal nerve supply the lower part of the breast, but there seems no direct branch to the NAC [11]

A deep branch from the anterior division of the 4th lateral cutaneous branch is reported to innervate the NAC by taking a course along the superficial fascia and building a plexus underneath the areola [11]

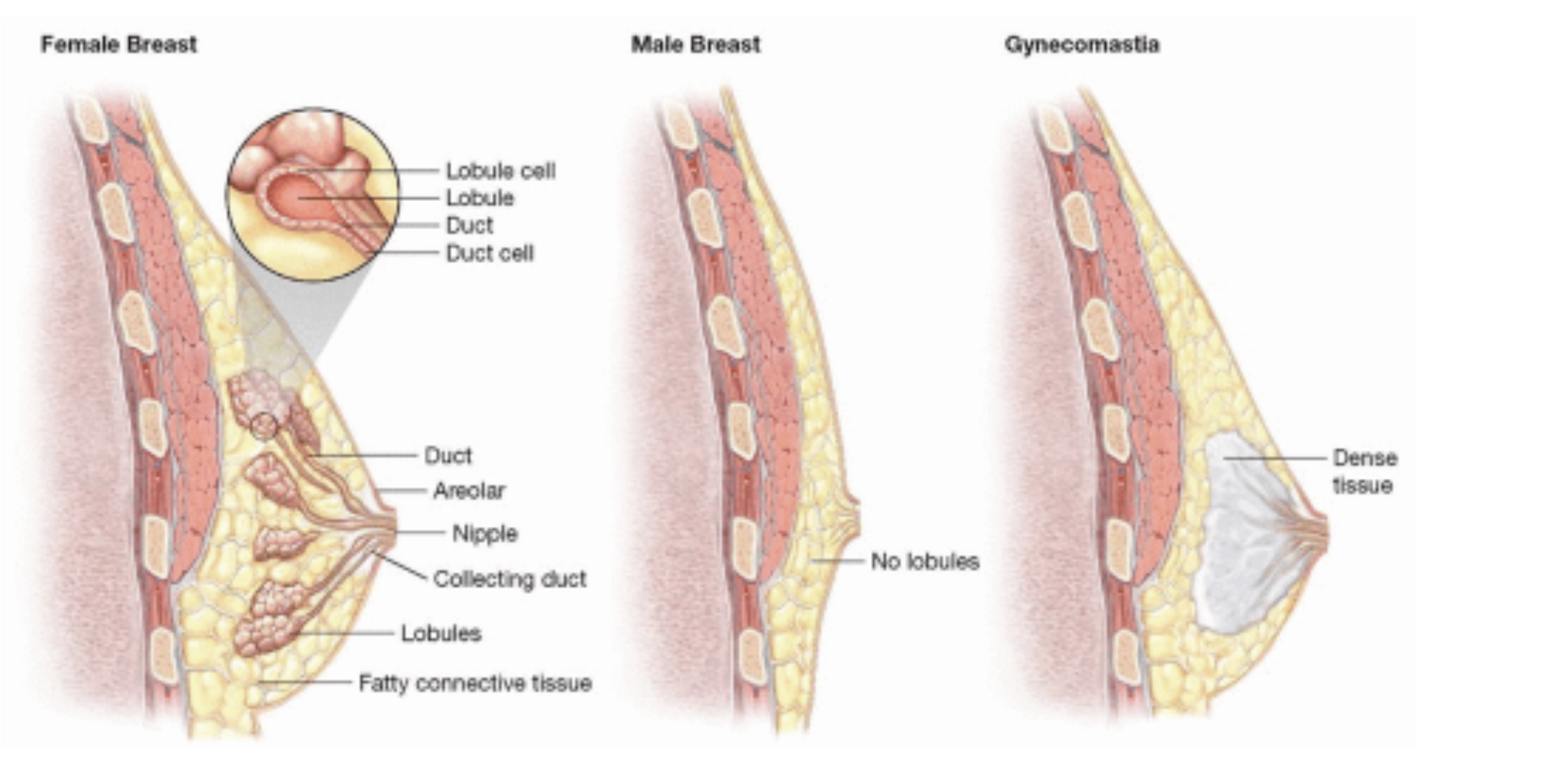

Composition of the male breast tissue

Female breast - Regular male breast - Gynecomastia

The male breast without gynecomastia mainly consists of fatty tissue with sporadic appearance of ducts and stroma [12].

Bannayan et al. histologically classfied the true gynecomastia into florid (ductal hyperplasia and proliferation), fibrous (more stromal fibrosis and fewer ducts) and intermediate gynecomastia [13].

In Contrast to female breast tissue lobules are generally absent [12].

Beside the lipomatous gynecomastia (pseudo-gynecomastia) which is more frequent in older patients, the histological type of the true gynecomastia also seems to be associated with age. Investigations by Fricke et al. showed that the rate of florid gynecomastia increased with the age of patients, while fibrous gynecomastia was more common in adolescents and young adults. The florid one seems to show a higher recurrence rate compared to the fibrous one [14].

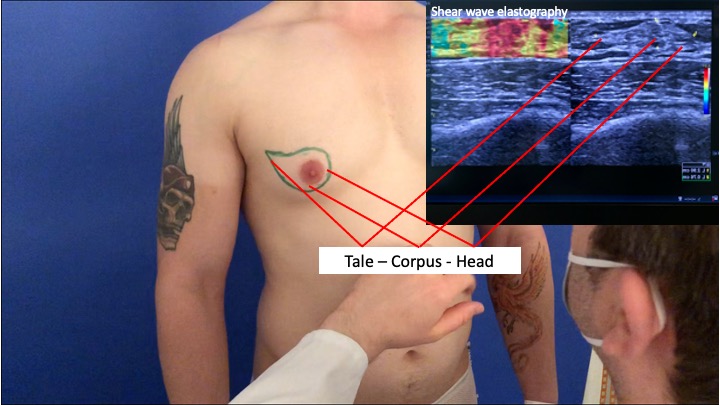

Blau et al. demonstrated in their investigations that the male breast gland is composed of a head, body and tail. The head is semicircular medial to the areola, the body is located beneath the areola and the tail goes along to the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major muscle [3].

Bannayan et al. histologically classfied the true gynecomastia into florid (ductal hyperplasia and proliferation), fibrous (more stromal fibrosis and fewer ducts) and intermediate gynecomastia [13].

In Contrast to female breast tissue lobules are generally absent [12].

Beside the lipomatous gynecomastia (pseudo-gynecomastia) which is more frequent in older patients, the histological type of the true gynecomastia also seems to be associated with age. Investigations by Fricke et al. showed that the rate of florid gynecomastia increased with the age of patients, while fibrous gynecomastia was more common in adolescents and young adults. The florid one seems to show a higher recurrence rate compared to the fibrous one [14].

Blau et al. demonstrated in their investigations that the male breast gland is composed of a head, body and tail. The head is semicircular medial to the areola, the body is located beneath the areola and the tail goes along to the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major muscle [3].

Shear wave elastography of the male gland

Body, head, tail of male gland

03

Etiology and Pathology

Etiology and Pathology

The true gynecomastia is differentiated from the so-called pseudo-gynecomastia (hypertrophy of fatty tissue) and contains true glandular tissue including ducts and stroma (no lobules). It is the most common breast alteration in males and occurs particularly during infancy, puberty and old age [15, 16].

The true gynecomastia is often related to a relative or absolute estrogen excess and/or a decrease of circulating androgen respectively a defect in androgen receptors.

Prevalence rates as reported by Johnson et al.:

The true gynecomastia is often related to a relative or absolute estrogen excess and/or a decrease of circulating androgen respectively a defect in androgen receptors.

Prevalence rates as reported by Johnson et al.:

Newborns: 60–90 %

Adolescents: 50–60 %

Men between 50 and 69 years: 70 %

The physiologic gynecomastia (25%) as part of normal physiologic changes is differentiated from the non-physiologic gynecomastia (50%) which is induced by pathological causes or drugs (see table below). The cause of the idiopathic gynecomastia mostly remains unclear (25%) [17]. Gynecomastia particularly in newborns and adolescents disappears spontaneously within months or years [18].

The histological appearance is reported to change with duration of symptoms[13]:

The histological appearance is reported to change with duration of symptoms[13]:

Florid: <4 months

Intermediate: 4-12 months

Fibrous: >12 months

Spontaneous regression of fibrous gynecomastia is regarded as unlikely. Thus, surgical treatment of gynecomastia is recommended after >12 months of persistence [18, 19].

Physiological gynecomastia

Transient neonatal gynecomastia

60-90 % of neonates due to transplacental transfer of maternal oestrogens

Transient pubertal gynaecomastia

50-60 % of adolescents, between ages 12 -14 to 19-21, typically lasting 6-12 months, spontaneous regression 90% due to disparity of estrogen/testosterone levels and increased sensitivity to estrogen 5-8.

Age related gynaecomastia

up to 70 % of men ages over 65, likely related to reduced testosterone levels and testicular involution 2, 9.

Pathological causes of gynecomastia

Gonadal failure

Primary hypogonadism due to trauma, chemotherapy, inflammatory damage, chromosomal aberration as Klinefelter Syndrome. In Klinefelter’s syndrome the reported incidence of gynecomastia syndrome ranges between 56% and 88% 10.Secondary hypogonadism due to hyperprolactinaemia or hypothalamic-pituitary axis, leading to lack of stimulation (pituitary adenomas).

Thyroid dysfunction

Hyperthyroidism leads to increase of sex hormone binding globulin, reducing free testosterone. Cause of gynecomastia in 10-40% of cases [27]. Early regulation to euthyroid state can resolve gynecomastia.

Renal insufficiency

Caused by suppression of testosterone production and possibly by direct testicular damage due to uremia[28]

Hormone secreting tumours

Estrogen secreting (Sertoli cell tumor, Leydig cell tumor), human chorionic gonadotrophin secreting tumors – in 7-11% of testicular tumors gynecomastia is the only symptom[29, 30], Testicular tumors are present in 3% of men with gynecomastia[31, 32].

Obesity

More often associated to pseudo-gynecomastia but also results in high levels of leptin and aromatase activity, increasing estrogen levels[33]

Other conditions

Ulcerative colitis; Cystic fibrosis; Refeeding syndrome after a prolonged period of malnutrition; Testicular infiltration-tuberculosis haemochromatosis

Drugs known to induce gynecomastia [34-37]

Antiandrogens

bicalutamide, flutamide, finasteride, dutasteride (AA)

Antiretrovirals

protease inhibitors (saquinavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, lopinavir), reverse transcriptase inhibitors (stavudine, zidovudine, lamivudine) (UM), efavirenz (UM)

Antihypertensives

calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, nifedipine, verapamil) (UM)

spironolactone (AA) -(as one of the most frequent causes)

spironolactone (AA) -(as one of the most frequent causes)

Environmental exposures

phenothrin (antiparasitical)

Exogenous hormones

oestrogens (EP), prednisone (male teenagers), human chorionic gonadotrophin (E)

Gastrointestinal drugs

H2 histamine receptor blockers (cimetidine) (AA), proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole) (AA)

Analgesics

opioid drugs (RA)

Antifungals

ketoconazole (prolonged oral use) (AA)

Antipsychotics (first generation)

haloperidol (IP), olanzapine, paliperidone (high doses), risperidone (high doses), ziprasidone

Chemotherapy drugs

methotrexate, alkylating agents—eg, cyclophosphamide, melphalan (AA); carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, bleomycin, cisplatin (AA), vincristine (AA), procarbazine

Exogenous hormones

androgens (misuse by athletes) (EP)

Cardiovascular drugs

phytoestrogens (soya based products, high quantity) (EP)

Recreational/illicit substances

marijuana, amphetamines (UM), heroin (UM), methadone (UM), alcohol

Herbals

lavender, tea tree oil, dong quai (female ginseng), Tribulus terrestris, soy protein (300 mg/day), Urtica dioica (common nettle)

AA=antiandrogenic; RA=reduced androgens; E=oestrogenic; IAM=increased androgen metabolism; ISHBG=increased concentration of sex hormone binding globulin; IP=increased prolactin; UM=unknown mechanism

Overview modified from Paul Thiruchelvam et al. "Gynecomastia" - Clinical updates - BMJ 2016;354:i4833 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4833

04

Male breast cancer

Male breast cancer

Male breast cancer is a very rare disease and represents less than 1-2% of all malignancies in men and less than 1% of all breast cancers [25]:

Lifetime risk: 1/1000 [25]

Median age at diagnosis in US: 62.4 years (vs. 58.2 in women) [25]

> 35 years the incidence increases sharply and does not show a midlife decline as observed in women [26]

Particular patient groups with high risk factors show increased incidences [25,26]:

Mutation in BRCA-2 gene increases the incidence by 80-100 times (Lifetime risk: 6.9%)

Klinefelter Syndrome increases the incidence by 20-50 times (low androgen and high gonadotropin levels due to atrophic testes)

Positive family history of breast cancer (33% of all male breast cancer patients within families with positive family history for breast or ovarian cancer )

Due to the low incidence of male breast cancer in patients without high risk factors it seems reasonable to treat gynecomastia using liposuction or surgical excision. In those with high risk factors as BRCA-2 mutation or Klinefelter syndrome excisional techniques are preferred [27].

05

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anamnesis

Onset time

Course of development

Drug history

History of associated co-diseases

Pharmaceuticals

Alcohol

Drugs

Family history with regards to cancer

Exposition to radiation

Examination

Body mass index

Bilateral comparative breast palpation including the axilla 3:

Supine position with arms resting behind head

Palpation with regards to painfulness, size and resistance

Size evaluation and documentation for follow up

> 2 cm in a concentric glandular mass is most consistent with true gynecomastia

< 2cm is defined as breast tissue which increases with age and adiposity

Suspicious breast masses (unilateral, decentral, painless, peau d'orange, rapid growth) -> referral to breast specialist

Testicular examination with respect to hypogonadismus or testicular masses

Consider Klinefelter syndrome

Technical Investigations

If breast tissue increased gradually and physiological gynecomastia seems reasonable no further investigations are required. For all other cases where no underlying cause can be determined further investigations are recommended.

Blood tests [40]

Standard tests: testosterone, estradiol, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), α-fetoprotein, ß-hCG, GOT, creatinine

Thyroid function: TSH, T3, T4

Suspicion of Klinefelter: chromosomal analysis

Imaging [40]

Imaging of the male breast:

Standard: Ultrasound is generally recommended also with regards to the differentiation between true gynecomastia and lipomastia.

In line with US guidelines further imaging investigation is only required where physical examination is unclear or suspicious 12. Therefore Mammography is the method of choice 13. Due to the fact that the incidence of gynecomastia associated breast cancer is reported with 0-2.5% mammography is rarely required 14.

Further Imaging:

Standard: Ultrasound is generally recommended also with regards to the differentiation between true gynecomastia and lipomastia.

In line with US guidelines further imaging investigation is only required where physical examination is unclear or suspicious 12. Therefore Mammography is the method of choice 13. Due to the fact that the incidence of gynecomastia associated breast cancer is reported with 0-2.5% mammography is rarely required 14.

Further Imaging:

Standard: testicular ultrasound is always recommended

Suspicion of a tumor of the adrenal glands (estradiol ↑, LH↓) : abdominal ultrasound, Ct-scan,12.

Suspicion of pituitary adenoma (prolactin↑, LH+FSH ↓): MRI

06

Clinical and Operative Algorithm

Clinical and operative Algorithm

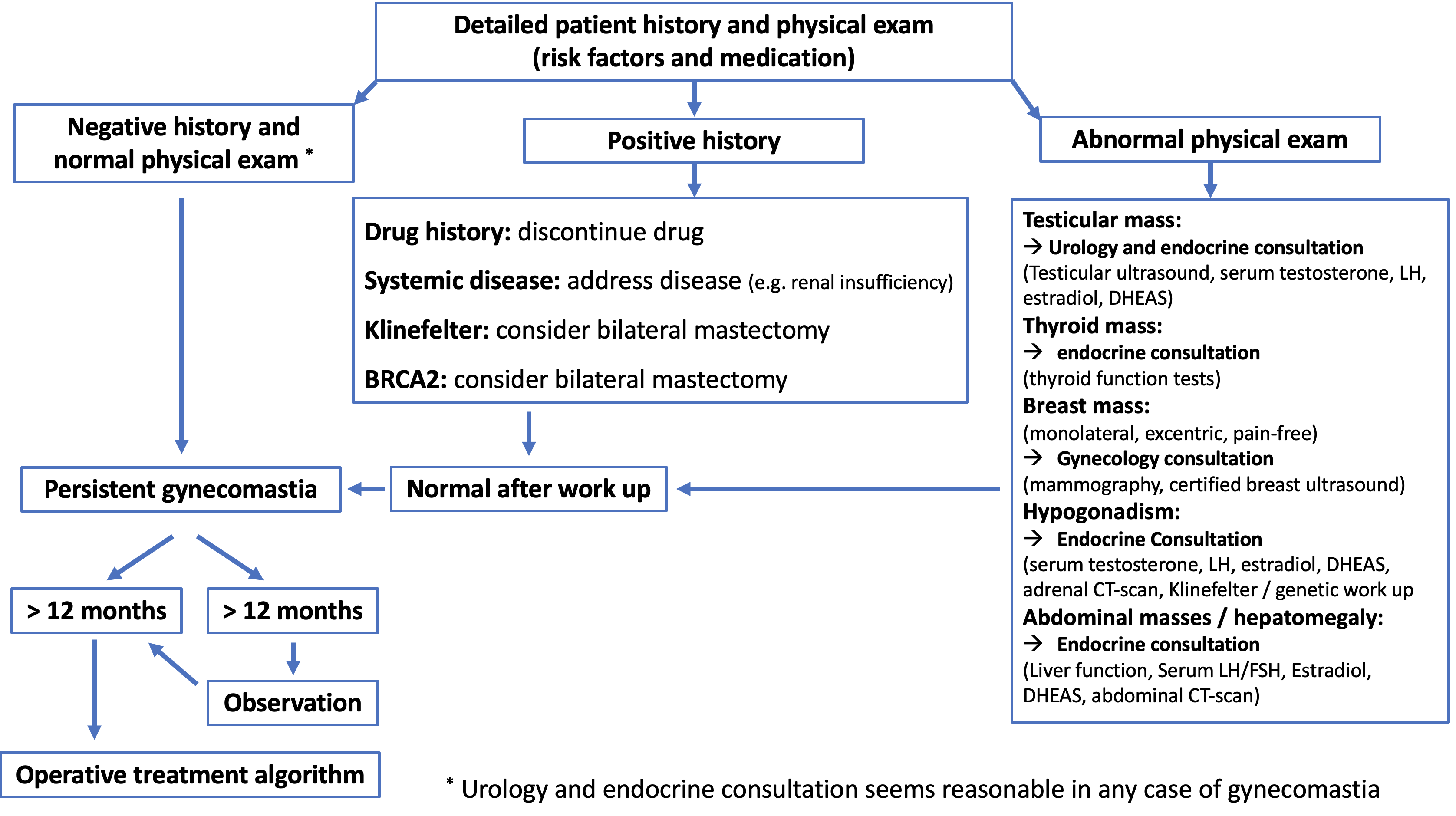

Clinical Algorithm

Clinical algorithm (modified from: Rohrich, R.J., et al., Plast Reconstr Surg, 2003. 111(2): p. 909-23; discussion 924-5.)

Operative Treatment Algorithm

Authors preferred operative management

07

Classifications

Classifications

Clinical Classifications

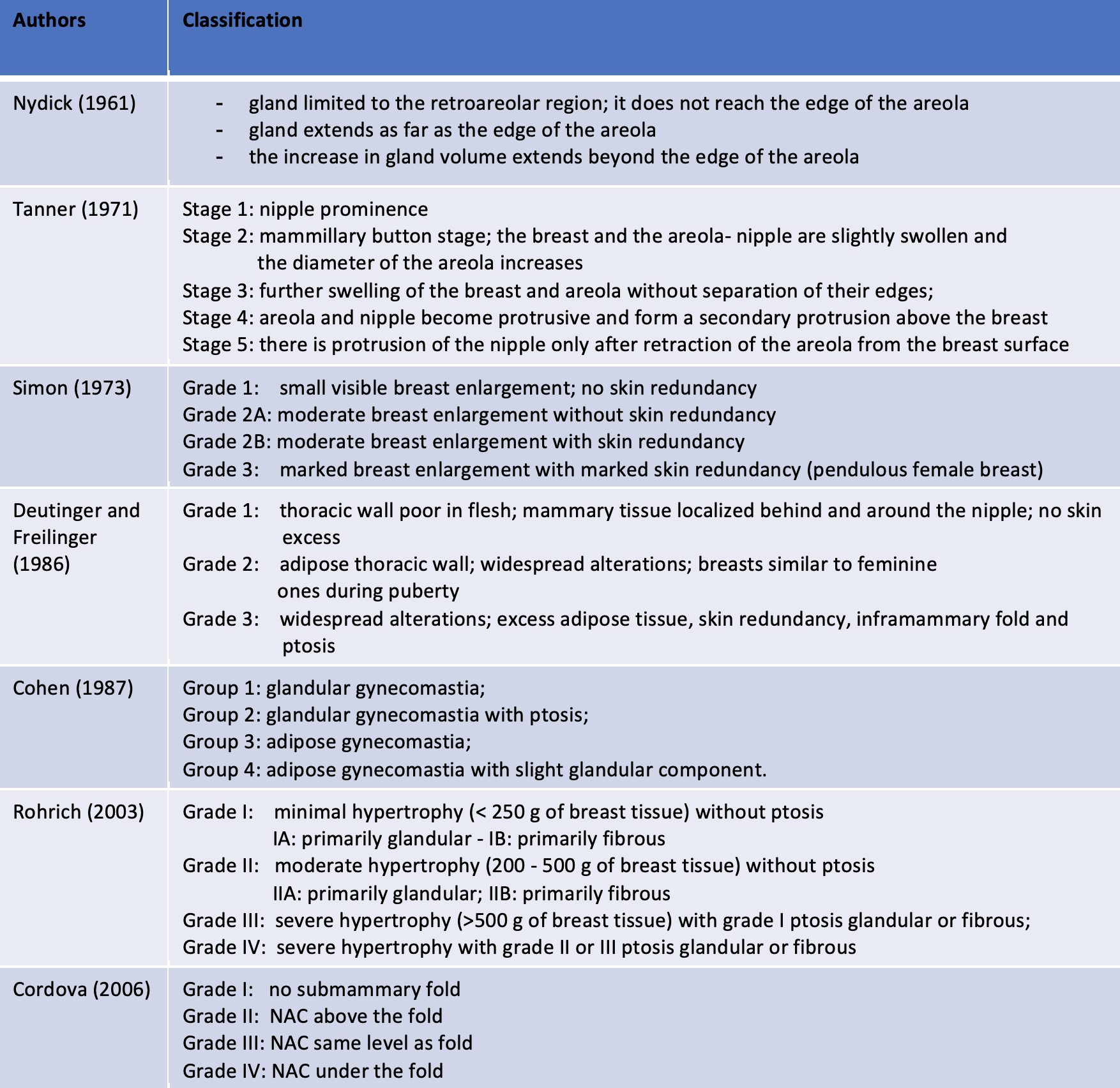

Classification History

Classification History (modified from: Cordova et al.;J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(1):41-9. doi: 10.1016)

Authors preferred Classification

The value of a classification is depending on its reproducible clinical implementation as well as on its medical consequences.

For a reproducible clinical assessment of gynecomastia particular limitations are the grading of skin laxity as well as the grading of fibrosis.

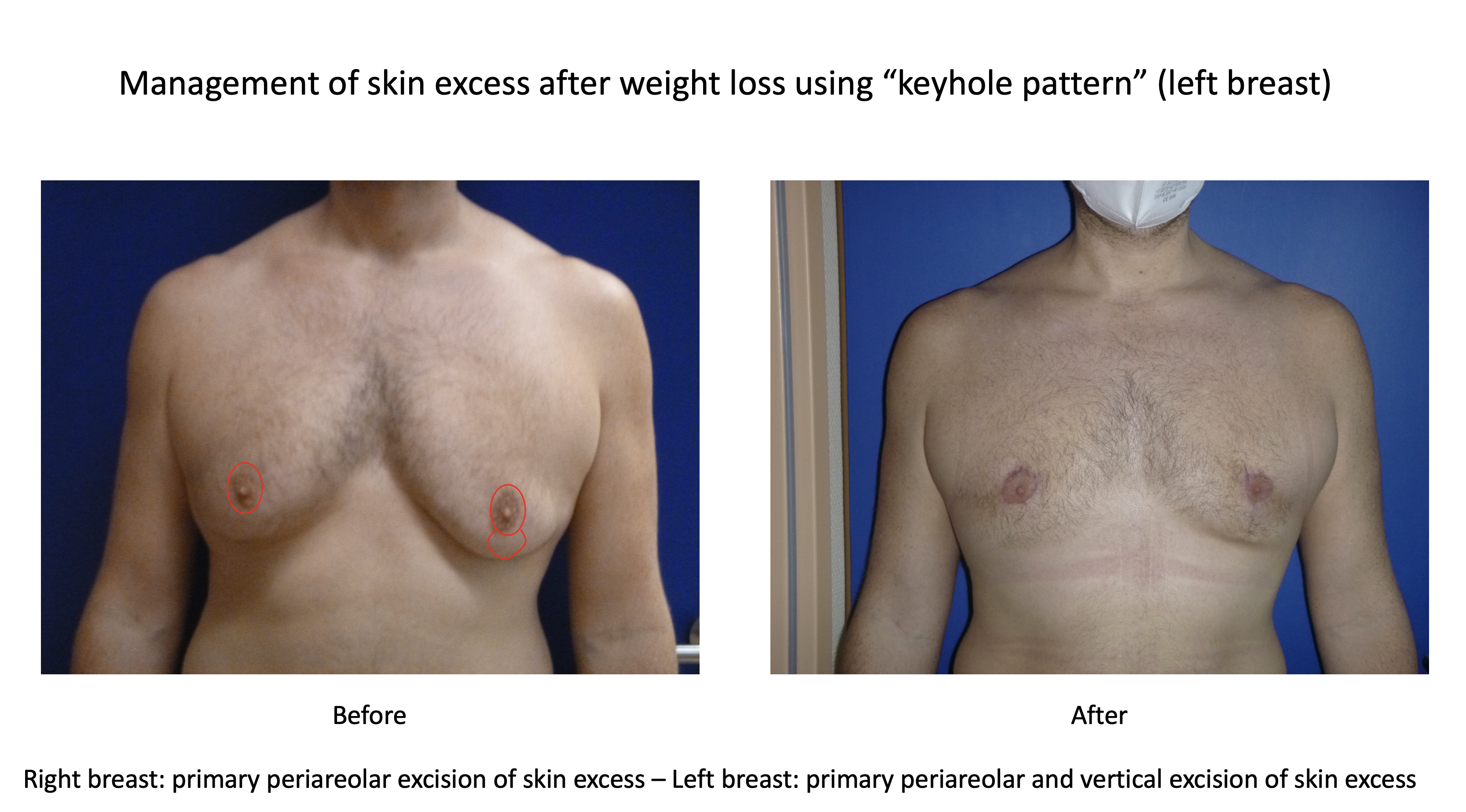

We stated that skin laxity after massive weight loss is highly reduced, and that one year after massive loss no further skin shrinking is expectable. Thus, we divided gynecomastia patients into two classes: with/without massive weight loss.

According to our preferred treatment algorithm subclasses with regards to fibrosis and skin excess were defined.

Although biopsy or ultrasound elastography could theoretically verify the grade of fibrosis subjective assessment remains as most practicable in clinical routine.

In patients without massive weight loss skin shrinking is expectable and thus should be awaited over 12 months.

If the MAC is stretchable 4 cm below the caudal border of the pectoralis major muscle the skin excess is sufficient to perform a horizontal mastectomy with fixation of the planned infrapectoral fold and transfer of the MAC 2 cm above.

In patients with massive weight loss and just moderate skin excess (not stretchable 4 cm below the pectoralis major muscle) a vertical skin excision is adequate.

For a reproducible clinical assessment of gynecomastia particular limitations are the grading of skin laxity as well as the grading of fibrosis.

We stated that skin laxity after massive weight loss is highly reduced, and that one year after massive loss no further skin shrinking is expectable. Thus, we divided gynecomastia patients into two classes: with/without massive weight loss.

According to our preferred treatment algorithm subclasses with regards to fibrosis and skin excess were defined.

Although biopsy or ultrasound elastography could theoretically verify the grade of fibrosis subjective assessment remains as most practicable in clinical routine.

In patients without massive weight loss skin shrinking is expectable and thus should be awaited over 12 months.

If the MAC is stretchable 4 cm below the caudal border of the pectoralis major muscle the skin excess is sufficient to perform a horizontal mastectomy with fixation of the planned infrapectoral fold and transfer of the MAC 2 cm above.

In patients with massive weight loss and just moderate skin excess (not stretchable 4 cm below the pectoralis major muscle) a vertical skin excision is adequate.

Authors preferred Classification

Histological Classification

Beside the division between the pseudo-gynecomastia (lipomatous gynecomastia) and true gynecomastia Bannayan et al. histologically classified the true gynecomastia [13]:

Histological type of gynecomastia

Composition

Florid gynecomastia

ductal hyperplasia and proliferation

Intermediate gynecomastia

ductal proliferation and stromal fibrosis

Fibrous gynecomastia

more stromal fibrosis

08

Conservative Treatment

Conservative Treatment

Due to the fact that gynecomastia is transient in 90% of adolescent patients it is recommended to wait until symptoms remain unchanged for 1-2 years before indicating any treatment [16, 18]. In cases where gynecomastia is induced by drugs or pathological reasons causative medication should be withdrawn and pathological findings should be addressed [16-19]. Thereby early acting within the early florid state of gynecomastia is crucial before glandular tissue will be replaced by irreversable fibrosis [16].

As conservative treatment pharmaceuticals can be highly effective before glandular fibrosis occurs.

Even not licensed for the treatment of gynecomastia Tamoxifen is the most popular medical treatment with response rates up to 95% [42-47].

The main indication for Tamoxifen is breast pain in gynecomastia smaller than 4 cm [19, 43].

Limiting side effects of Tamoxifen are[48]:

As conservative treatment pharmaceuticals can be highly effective before glandular fibrosis occurs.

Even not licensed for the treatment of gynecomastia Tamoxifen is the most popular medical treatment with response rates up to 95% [42-47].

The main indication for Tamoxifen is breast pain in gynecomastia smaller than 4 cm [19, 43].

Limiting side effects of Tamoxifen are[48]:

thromboembolic events (31%)

loss of libido (23%)

bone pain (15%)

neurocognitive deficits (15%)

leg cramps (8%)

ocular events (8%)

09

Operative Treatment

Operative Treatment

Liposuction

Conventional suction assisted liposuction (SAL) or water-jet assisted liposuction (WAL) are suitable to address the fatty tissue around the glandular mass:

Preoperative marking in standing position with respect to the extent of gynecomastia (head, body, tail), course of the pectoralis major muscle and axillary adhesion zones

General or local anesthesia

Supine position with arms abducted

Short lateral incision using an 11 blade within the infra-pectoral fold

In combination with a surgical excision two further periareolar incisions (3:00/09:00) can be useful

Liposuction using 4.2 and 3.5 mm cannulas (3.5mm for final conturing)

In case of extensiv liposuction placement of drains using the lateral incisions may be reasonable

If available, the treatment of the glandular mass by the use of ultrasound assisted liposuction (UAL) is reported to be highly effective [18, 48].

Subcutaneous mastectomy via periareolar incision

Periareolar and vertical skin excision (moderate skin excess after massive weight loss)

Management of skin excess using keyhole pattern

Horizontal mastectomy

10

Perioperative management

Perioperative management

Preoperative management

Discontinuation or conversion of anticoagulants - if possible

Nicotine abstinence 6 weeks before and after surgery

Customization of a compression vest or other compression garment

Postoperative Management

Inpatient observation over 1 night with regards to secondary bleeding

Immediate compression therapy after surgery (compressive dressing or garment) for 6 weeks

Drain removal when output <30cc / 24h - if placed.

Weekly follow-up care over 4 weeks with regards to seroma - if required puncture aspiration.

11

Common complications and their management

Common complications and their management

Hematoma

Cause: Bleeding, predominantly lateral out of branches of the lateral thoracic artery

Prevention: Raising blood pressure before diathermy (systole above 120 mmHg) and use of drains

Problem solution: Surgical revision, if possible aspiration puncture and conpression

Seroma

Cause: Collection of serous fluid due to inflammatory reaction after surgery

Prevention and solution: Compression garment for 6 weeks - weekly follow-up with regards to seroma, if required aspiration puncture.

Saucer deformity:

Cause: Glandular excision directly beneath areola, big glandular mass

Prevention: Leave a tissue layer of 1-2 cm beneath areola during subcutaneous mastectomy, alignment to surrounding tissue by liposuction

Problem solution: Alignment to surrounding tissue by liposuction, if required retroareolar lipofilling

Horizontal deformity of the NAC

Cause: Too much periareolar skin excision lateral and medial

Prevention: periareolar resection pattern should be vertical-oval

Problem solution: wait and see, if required corrective periareolar cephalad and caudal resection or lipofilling

Periareolar wound healing disturbance

Cause: Too much skin resection

Prevention: Secondary skin excision (12 months after primary surgery) respectively conservative skin excision

Problem solution: wait secondary healing, if required subsequent revision

Non-alignment of scar and infra-pectoral fold after horizontal mastectomy

Cause: Cephalad distortion of the scar due to missing infra-pectoral fixation

Prevention and solution: Infra-pectoral fixation using PDS sutures, if required infra-pectoral liposuction

12

References

1. Kinsella, C., Jr., et al., The psychological burden of idiopathic adolescent gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2012. 129(1): p. 1-7.2. Beer, G.M., et al., Configuration and localization of the nipple-areola complex in men. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2001. 108(7): p. 1947-52; discussion 1953.3. Agarwal, C.A., et al., Creation of an Aesthetic Male Nipple Areolar Complex in Female-to-Male Transgender Chest Reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2017. 41(6): p. 1305-1310.4. Blau, M., R. Hazani, and D. Hekmat, Anatomy of the Gynecomastia Tissue and Its Clinical Significance. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open, 2016. 4(8): p. e854.5. Shulman, O., et al., Appropriate location of the nipple-areola complex in males. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2001. 108(2): p. 348-51.6. Wolter, A., et al., Sexual reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: an algorithm for subcutaneous mastectomy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2015. 68(2): p. 184-91.7. Lo Russo, G., S. Tanini, and M. Innocenti, Masculine Chest-Wall Contouring in FtM Transgender: a Personal Approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2017. 41(2): p. 369-374.8. Maas, M., et al., The Ideal Male Nipple-Areola Complex: A Critical Review of the Literature and Discussion of Surgical Techniques for Female-to-Male Gender-Confirming Surgery. Ann Plast Surg, 2020. 84(3): p. 334-340.9. Kasai, S., et al., An anatomic study of nipple position and areola size in Asian men. Aesthet Surg J, 2015. 35(2): p. NP20-7.10. Vaucher, R., et al., [Anatomical study of men's nipple areola complex]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet, 2016. 61(3): p. 206-11.11. Sarhadi, N.S., et al., An anatomical study of the nerve supply of the breast, including the nipple and areola. Br J Plast Surg, 1996. 49(3): p. 156-64.12. Misery, L. and M. Talagas, Innervation of the Male Breast: Psychological and Physiological Consequences. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia, 2017. 22(2): p. 109-115.13. Iuanow, E., M. Kettler, and P.J. Slanetz, Spectrum of disease in the male breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2011. 196(3): p. W247-59.14. Bannayan, G.A. and S.I. Hajdu, Gynecomastia: clinicopathologic study of 351 cases. Am J Clin Pathol, 1972. 57(4): p. 431-7.15. Fricke, A., et al., Gynecomastia: histological appearance in different age groups. J Plast Surg Hand Surg, 2018. 52(3): p. 166-171.16. Cuhaci, N., et al., Gynecomastia: Clinical evaluation and management. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2014. 18(2): p. 150-8.17. Johnson, R.E. and M.H. Murad, Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clin Proc, 2009. 84(11): p. 1010-5.18. Sansone, A., et al., Gynecomastia and hormones. Endocrine, 2017. 55(1): p. 37-44.19. Rohrich, R.J., et al., Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2003. 111(2): p. 909-23; discussion 924-5.20. Thiruchelvam, P., et al., Gynaecomastia. BMJ, 2016. 354: p. i4833.21. Akgul, S., N. Kanbur, and O. Derman, Pubertal gynecomastia: what about the remaining 10%? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 2014. 27(9-10): p. 1027-8.22. Biro, F.M., et al., Hormonal studies and physical maturation in adolescent gynecomastia. J Pediatr, 1990. 116(3): p. 450-5.23. LaFranchi, S.H., et al., Pubertal gynecomastia and transient elevation of serum estradiol level. Am J Dis Child, 1975. 129(8): p. 927-31.24. Ma, N.S. and M.E. Geffner, Gynecomastia in prepubertal and pubertal men. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2008. 20(4): p. 465-70.25. Niewoehner, C.B. and F.Q. Nuttal, Gynecomastia in a hospitalized male population. Am J Med, 1984. 77(4): p. 633-8.26. Wu, F.C., et al., Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(7): p. 2737-45.27. Smyth, C.M. and W.J. Bremner, Klinefelter syndrome. Arch Intern Med, 1998. 158(12): p. 1309-14.28. Tan, Y.K., C.R. Birch, and D. Valerio, Bilateral gynaecomastia as the primary complaint in hyperthyroidism. J R Coll Surg Edinb, 2001. 46(3): p. 176-7.29. Iglesias, P., J.J. Carrero, and J.J. Diez, Gonadal dysfunction in men with chronic kidney disease: clinical features, prognostic implications and therapeutic options. J Nephrol, 2012. 25(1): p. 31-42.30. Hendry, W.S., et al., Ultrasonic detection of occult testicular neoplasms in patients with gynaecomastia. Br J Radiol, 1984. 57(679): p. 571-2.31. Hernes, E.H., K. Harstad, and Fossa, Changing incidence and delay of testicular cancer in southern Norway (1981-1992). Eur Urol, 1996. 30(3): p. 349-57.32. Daniels, I.R. and G.T. Layer, Testicular tumours presenting as gynaecomastia. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2003. 29(5): p. 437-9.33. Harris, M., et al., Testicular tumour presenting as gynaecomastia. BMJ, 2006. 332(7545): p. 837.34. Dundar, B., et al., Leptin levels in boys with pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 18(10): p. 929-34.35. Bowman, J.D., H. Kim, and J.J. Bustamante, Drug-induced gynecomastia. Pharmacotherapy, 2012. 32(12): p. 1123-40.36. Dickson, G., Gynecomastia. Am Fam Physician, 2012. 85(7): p. 716-22.37. Karavolos, S., et al., Male central hypogonadism secondary to exogenous androgens: a review of the drugs and protocols highlighted by the online community of users for prevention and/or mitigation of adverse effects. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2015. 82(5): p. 624-32.38. Nuttall, F.Q., Gynecomastia. Mayo Clin Proc, 2010. 85(10): p. 961-2.39. Abdelwahab Yousef, A.J., Male Breast Cancer: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Semin Oncol, 2017. 44(4): p. 267-272.40. Thomas, D.B., Breast cancer in men. Epidemiol Rev, 1993. 15(1): p. 220-31.41. Schanz, S., et al., S1-Leitlinie: Gynakomastie im Erwachsenenalter. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2017. 15(4): p. 465-472.42. Alagaratnam, T.T., Idiopathic gynecomastia treated with tamoxifen: a preliminary report. Clin Ther, 1987. 9(5): p. 483-7.43. Derman, O., et al., Long-term follow-up of tamoxifen treatment in adolescents with gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 21(5): p. 449-54.44. Derman, O., N.O. Kanbur, and T.E. Tokur, The effect of tamoxifen on sex hormone binding globulin in adolescents with pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 2004. 17(8): p. 1115-9.45. James, R., F. Ahmed, and G. Cunnick, The efficacy of tamoxifen in the treatment of primary gynecomastia: an observational study of tamoxifen versus observation alone. Breast J, 2012. 18(6): p. 620-1.46. Konig, R., et al., [Treatment of marked gynecomastia in puberty with tamoxifen]. Klin Padiatr, 1987. 199(6): p. 389-91.47. Lawrence, S.E., et al., Beneficial effects of raloxifene and tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr, 2004. 145(1): p. 71-6.48. Pemmaraju, N., et al., Retrospective review of male breast cancer patients: analysis of tamoxifen-related side-effects. Ann Oncol, 2012. 23(6): p. 1471-4.49. Zocchi, M.L., Ultrasonic assisted lipoplasty. Technical refinements and clinical evaluations. Clin Plast Surg, 1996. 23(4): p. 575-98.

Images

Authors preferred Classification

Authors preferred operative management

Classification History (modified from: Cordova et al.;J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(1):41-9. doi: 10.1016)

Anatomy male breast

Composition of the female an male breast

Shear wave elastography of the male gland

Body, head, tail of male gland

Clinical algorithm (modified from: Rohrich, R.J., et al., Plast Reconstr Surg, 2003. 111(2): p. 909-23; discussion 924-5.)

Female breast - Regular male breast - Gynecomastia

Management of skin excess using keyhole pattern

Ideal position of the male nipple-areola complex.- Modified from Beer et. al., by Given et al. Plastische Chirurgie, 16. Jahrgang Heft 2/2016

Videos

Gynecomastia - Preoperative marking for subcutaneous mastectomy

Gynecomastia - Surgery video for subcutaneous mastectomy

Gynecomastia - Preoperative marking for horizontal mastectomy + free areola transplantation

Gynecomastia - Surgery video for horizontal mastectomy + free areola transplantation

References