["7133c666e0c66761eba8ba6aa924d6b5731459ff","3fc45fcb0150fc5ffe38505e522ee37edd4702aa"]

Skin tumors

basal cell carcinoma

squamous cell carcinoma

facial reconstruction

1825

1825

Chapter reads

0

0

Chapter likes

6/10

Evidence score

18

18

Images included

00

0

Videos included

01

Introduction

The skin is a complex organ that covers the complete surface of the human body. [13] Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer with UV-exposure being the most prevalent risk factor and the incidence is rising. There are multiple therapeutic options and plastic surgeons are receiving an increasing number of referrals for reconstruction of patients with complicated soft tissue lesions. Therefore knowledge of complications, cosmetic outcomes and recurrence rates is required. [15] [23]

02

Basics: Anatomy and function of the skin

The skin is the largest organ and it accounts for 15 % of the total body weight. It has three main vital functions:

• Protection (against external physical, chemical and biological aggressions)

• Regulation (body temperature, peripheral circulation and fluid balance)

• Sensation (as it includes an extensive network of nerve cells) [13]

• Protection (against external physical, chemical and biological aggressions)

• Regulation (body temperature, peripheral circulation and fluid balance)

• Sensation (as it includes an extensive network of nerve cells) [13]

Macroscopic anatomy

The macroscopic structure of the skin depends on the location in the body and the mechanical stress. Two types of skin can be found: meshed skin and ridged skin.

Meshed skin covers approximately 95 % of the body surface and includes appendages (e. g. sweat glands, sebaceous glands, hair).

Ridged skin makes up 4 % of the body surface and extends over the bottom of the feet and the palm of the hands. It includes only small sweat glands, is hairless and more resistant to pressure. [31] [2]

Furthermore tension vectors across the skin can be identified dependent of the volume and movement of the underlying structures. As a quantitative measurement of the skin tension is difficult, skin lines are used as a surrogate parameter for skin tension. The most common ones are Langer’s lines and relaxed skin tension lines. Langer’s lines run parallel to the main collagen bundles in the dermis. Relaxed skin tension lines are visible as wrinkles when the skin is pinched and released without local tension. The wrinkles occur in a 90° angel to the underlying muscle fibers. Over many parts of the body Langer’s lines and relaxed skin tension lines run the same, but in mechanically complex regions they differ from each other. [29] [4]

Microscopic anatomy

Microscopically the skin is arranged in three layers including the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis.

The epidermis is the most superficial stratum of the skin and consists of a multilayered keratinized squamous epithelium. The squamous epithelium is organized in five different layers, that are determined by the degree of the differentiation of the keratinocytes. From inside to outside the following zones can be found:

Stratum basale: keratinocytes are columnar or cubical and are aligned to the underlying basement membrane

Stratum spinosum: polygonal keratinocytes, cell membrane looks „spiky“ due to visible desmosome contacts

Stratum granulosum: keratinocytes are flattened, cells contain basophil keratohyaline granules, simultaneously loss of other cell organelles increases

Stratum lucidum: cells in transitional stages between ceratinocytes and corneocytes, visible as homogenous eosinophilic layer, only found in ridged skin

Stratum corneum: completely keratinized, non-vital cells without a cell nucleus or organelles

Moreover there are melanocytes, merkel cells and Langerhans cells in the epidermis. Melanocytes are located in the stratum basale, they provide melanin and store it in melanosomes. Merkel cells are also located in the stratum basale and serve as pressure receptors. Langerhans cells are based in the stratum spinosum and are antigen presenting cells. [22] [2] [13]

Just below the epidermis the dermis can be found. It consists mainly of connective tissue and the vascular and nervous plexuses are running through it. The dermis is arranged in two zones:

Stratum papillare: the papillary dermis forms conic upward projections (dermal papillae) to increase the surface of contact between epidermis and dermis. The connective tissue is organised in loose collagen bundles.

Stratum reticulare: consists of tight connective tissue with coarse collagen bundels and elastic fibers.

Besides vessels and nerve endings the dermis contains several cells including mast cells, dermal dendrocytes and macrophages. Furthermore also hair follicles are located in the reticular dermis. [22] [13]

The innermost layer is described as hypodermis and consists of loose connective tissue. It contains the epifascial vascular system as well as the cutaneous nerves. The subcutaneous adipose tissue is important for thermoregulation, insulation, nutritional and energy storage. Furthermore it serves as protection from mechanical stress. [13] [22]

03

Benign Skin Tumors

As in every other tissue the skin can also develop tumors. It is important to know whether the skin tumors are benign or malignant. If cells pass the basal membrane and spread to other tissues, tumors are considered malignant. [8] There is a large number of different benign skin lesions. this chapter is intended to provide an overview of the most common ones.

General information and overview

Benign neoplasms of the skin can develop from different tissues or cells of the skin e. g. the epidermis or the dermal appendages. The diagnosis is usually made with the help of a clinical examination and the patient’s history. For any lesions with uncertain diagnosis a biopsy should be scheduled to rule out malignancy. Some of these neoplasms may be an indicator for internal disease or genetic syndromes. [12] [14]

With regard to the literature there are different classifications. The following table shows a histological classification of common benign skin tumors. [8] [14] [12]

Epidermal tumors

seborrhoic keratosis, fibroma pendulans, epidermal nevi

Tumors of the dermal appendages

Benign follicular tumors

trichoepithelioma, pilomatricoma, trichofolliculoma, dilated pore of Winer

Benign sebaceous tumors

sebaceous hyperplasia

Benign tumors of the perspiratory glands

syringoma, apocrine hidrocystomas, eccrine hidrocystomas

Cysts

epidermoid cysts, trichilemmal cyst, myxoid cyst, milium

Mesodermal and subcutaneous tumors

dermatofibroma, lipoma, keloid, hypertrophic scars

Vascular tumors or malformations

hemangioma, nevus flammeus, cherry angioma, angiokeratoma

Although a routine removal is not necessary due their benign nature, patients may wish excision due to aesthetic or symptomatic distress. There are multiple forms of therapy available, including excision, cryotherapy, curettage, laser therapy and pharmacotherapy. Treatment is based on the type of tumor and its location. For lipomas, dermatfibromas, keratoacanthomas and peridermoid cysts excision is the treatment of choice. Furthermore treatments for cherry angiomas and sebaceous hyperplasia are laser therapy and electrodesiccation. Seborrheic keratoses is often treated with cryotherapy or shave excision. [21] [12]

Common benign skin lesions

Seborrhoic keratosis / seborrheic verruca

Epidemiology

One of the most common benign skin tumors, especially in elderly persons

Increasing prevalence over the course of life, independent of external factors [8]

Clinical presentation

Common characteristics: brown or black papula / plaque with clear borders, diameter ranges from 5 millimeters to over 5 centimeters

Typical localization: face, upper body, lower arm, dorsum of the hand

No tendency to degenerate, may bleed after mechanical irritation [8]

Diagnostic

: direct-light microscopy: visible keratin cysts [8]

: direct-light microscopy: visible keratin cysts [8]

Therapy

: as seborrheic keratosis is a benign skin tumor a treatment is not necessary. Nevertheless many patience wish a removal of the tumor for cosmetic reasons. [8]

: as seborrheic keratosis is a benign skin tumor a treatment is not necessary. Nevertheless many patience wish a removal of the tumor for cosmetic reasons. [8]

Epidermoid cyst

Epidemiology: most common type of cuteaneous cyst [12]

Clinical presentation

Common characteristics: cyst surrounded by an epithelial wall that contains keratin and is linked to the skin surface via a excretory duct, appears as slow growing subcutaneous nodule.

Typical Localization: head, neck, trunk.

Epidermoid cysts are associated with Gardener syndrome. [12]

Diagnostic

: epidermal cysts can be diagnosed via clinical examination. After excision diagnosis is confirmed via histopathological examination.

: epidermal cysts can be diagnosed via clinical examination. After excision diagnosis is confirmed via histopathological examination.

Therapy

: a treatment is not necessary. If desired, the definitive treatment is a complete excision of the cyst. Excision should be performed when the lesion is not inflamed. (It is suggested to wait 4 – 6 weeks after the inflammation has resolved) [12]

: a treatment is not necessary. If desired, the definitive treatment is a complete excision of the cyst. Excision should be performed when the lesion is not inflamed. (It is suggested to wait 4 – 6 weeks after the inflammation has resolved) [12]

Trichilemmal cyst (pilar cyst)

Epidemiology

Second most common type of cuteaneous cyst

Presence in 5 % - 10 % of the population

Occur more often in females [12]

Clinical presentation

Common characteristics: cyst surrounded by an epithelial wall that contains keratin, appears as slow growing subcutaneous nodule, can grow up to 5 cm

Typical Localization: scalp [12]

Diagnostic

: trichilemmal cysts can be diagnosed via clinical examination. After excision diagnosis is confirmed via histopathological examination.

: trichilemmal cysts can be diagnosed via clinical examination. After excision diagnosis is confirmed via histopathological examination.

Therapy

: a treatment is not necessary. If desired, the definitive treatment is a complete excision of the cyst. [12]

: a treatment is not necessary. If desired, the definitive treatment is a complete excision of the cyst. [12]

Sometimes epidermoid cysts and trichilemmal cysts are referred to as sebaceous cysts. This is a misnomer as they both arise from entrapment of surface epithelium into the dermis. [14]

Fibroma pendulans

Epidemiology

Presence in 50 % - 60 % of adult persons

Often development of fibromas start during puberty [8]

Clinical presentation

Common characteristics: soft skin-colored papulas (often attached to skin via a pedicle)

Typical localization: fibromas develop often at mechanically stressed areas

In case of increased occurrence they can be a pointer to obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance or other signs of metabolic syndrome. [8]

Diagnostic

: fibromas can be diagnosed via clinical examination.

: fibromas can be diagnosed via clinical examination.

Therapy

: a treatment is not necessary. Surgical excision is possible, in case of painful or aesthetic disturbing fibromas with scissors only, often even placing sutures is unnecessary.[8]

: a treatment is not necessary. Surgical excision is possible, in case of painful or aesthetic disturbing fibromas with scissors only, often even placing sutures is unnecessary.[8]

04

Malignant Skin Tumors

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer. It usually occurs in sun-exposed areas of the skin. As the incidence is inversely proportional to the melanin content of the skin, fair-skinned persons have a higher risk.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant skin cancer. (About 8 out of 10 skin cancers) It has a low mortality but can cause significant local destruction. [15]

Risk factors

Genetic predisposition: Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (Lifetime risk is estimated at 30 %), male gender

Genetic diseases: basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism, t-cell linked immune deficiencies, Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome

Immunosuppression (e. g. post organ transplant or HIV-positive patients)

External factors: UV exposition (in particular chronic or intermittently strong exposition, can lead to mutations of TP53, prolonged latency), chemical noxae (e. g. Arsen), ionizing radiation (BCC can develop from radiation dermatitis), chronic wounds [15]

Pathogenesis

Cell growth is regulated by the intracellular hedgehog signaling pathway. A permanent activation of this pathway can cause tumor formation. The most common mutations leading to basal cell carcinoma development are inactivation mutations of PTCH1 gene or activating mutations of SMO gene. [15]

Histological subtypes

Lower-Risk subtypes: superficial basal cell carcinoma, nodular basal cell carcinoma (most common variant), pigmented basal cell carcinoma

Higher-risk subtypes: morpheaform (= sclerodermiform) basal cell carcinoma, infiltrative basal cell carcinoma, micronodular basal cell carcinoma, basosquamous (behaves more similar to squamous cell carcinoma) [15]

Clinical presentation

Variable appearance

Appearance is influenced by progression, histological subtype, localization

Common characteristics: plaque or nodus with a central lower area, raised edges and telangiectasia, might bleed after minor injuries

Typical localization: sun-exposed areas like face (in particular nose), head and neck, can only develop in skin regions that contain hair follicles

Usually slow growing, metastasis is rare (median time interval between primary tumor and development of metastases is nine years) [16] [5]

Diagnostic

History: previous skin tumors, UV exposition, pre-existing disease, long-term medication (notably immunosuppression), family history

Clinical examination: inspection (see common characteristics), palpation (especially local lymphatic nodes)

Instrument-based diagnostic: dermatoscopy (each histological subtype has typical findings), confocal laser scanning microscopy, optical coherence-tomography

Biopsy --> diagnostic confirmation, decision which therapy is suitable

Staging: In case of suspected metastases a MRI can be performed [16]

Therapy

As basal cell carcinomas have a low metastatic potential the therapeutic target is local control.

Surgical therapy

First line therapy is surgical excision, as a total removal of the carcinoma has the best prognosis. (95 % 5-year cure rate) There are different options for surgical excision:

Conventional excision: excision margin should measure 4 – 6 mm, the margin simply has to be confirmed “negative” = R0 in histologic examination

Mohs micrographic surgery: treatment of choice for high risk and recurrent basal cell carcinomas

Shave excision: only for small and superficial basal cell carcinomas possible, might be considered in large body areas affected by adjacent skin tumors (e.g. scalp)

Radiotherapy

If a complete removal seems unlikely (due to location, local growth, age or comorbidity of the patient) or surgical excision is rejected by the patient, radiotherapy can be performed

Furthermore irradiation can be offered for patients with contraindications for surgical therapy.

Radiation treatment should not be used in patients with diseases associated with increased radiation sensitivity (e. g. lupus erythematosus, basal cell carcinoma syndrome)

Topical medication

For low-risk basal cell carcinomas and elderly multimorbid patients topical medications is a therapeutical option

Advantages are: application at home is possible, good cosmetic results (avoiding scars)

Imiquimod 5 % cream and 5-fluorouracil can be used to treat superficial basal cell carcinomas, especially if surgical therapy is contraindicated

Systemic medication

In patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma therapy with a hedgehog inhibitor and inclusion in a clinical trial should be discussed by an interdisciplinary tumor board

In patients with multiple basal cell carcinomas (e. g. in the context of a basal cell carcinoma syndrome) treatment with a hedgehog inhibitor should be offered

In case of locally advanced basal cell carcinoma neoadjuvant therapy with a hedgehog inhibitor should be considered

Further therapeutical options: cryosurgery, laser-based therapy.

Surgical therapy is the only therapy that allows a histological confirmation of the diagnosis.

Surgical therapy is the only therapy that allows a histological confirmation of the diagnosis.

Aftercare

A standardized follow-up of patients with basal cell carcinomas is used for early detection of local tumor recurrence and identification of secondary tumors

Surgically treated basal cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas with low risk of recurrence: follow-up after 6 months, afterwards once a year

Multiple basal cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas with high risk of recurrence: follow-up every 3 months. If more than two years no new basal cell carcinoma or recurrence has occurred follow-up once a year. [17]

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Squamous cell carcinomas occur when growth of the keratinocytes of the epidermis is out of control. It is the second most common skin cancer. (Squamous cell carcinomas represent 20 % of skin cancer) [32]

Risk factors

Genetic predisposition: Fitzpatrick skin types I and II, male gender

Genetic diseases: xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism, epidermolysis bullosa hereditarian, Muir-Torre syndrome

Precancerosis: actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease, erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowenoid papulosis

• Immunosuppression (e. g. post organ transplant or HIV-positive patients) --> Most common malignant tumor post organ transplantation

• Immunosuppression (e. g. post organ transplant or HIV-positive patients) --> Most common malignant tumor post organ transplantation

External factors: UV exposition (can lead to mutations of TP53 or H-Ras oncogene), chemical noxae (e. g. Arsen), ionizing radiation (SCC can develop from radiation dermatitis), chronic wounds [32] [25]

Histological subtypes

Lower-risk subtypes: keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, clear cell SCC

Higher-risk subtypes: acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, adenosquamous carcinoma [32]

Clinical presentation

Often pre-existing precancerosis (most commonly actinic keratosis) or chronic wound / scar

Common characteristics: nodus with a central ulceration, painless, tendency to bleed after minor injuries

Typical localization: sun-exposed areas like face (in particular forehead, auricle, lips) or forearm, hand or mucosa (mouth, genital area)

Can be local destructive (infiltration of tendon, muscles and bones is possible), metastasis is rare (mainly lymphatic metastasis) [25] [11]

Diagnostic

History: previous skin tumors, UV exposition, pre-existing disease, pre-existing skin lesions, long-term medication (notably immunosuppression), family history, occupation

Clinical examination: inspection (see common characteristics), palpation (especially local lymphatic nodes)

Instrument-based diagnostic: dermatoscopy, optical coherence-tomography (differentiation between SCC, BCC, actinic keratosis)

Incisional biopsy --> diagnostic confirmation

Staging: sonography of locoregional lymphnodes, cross-sectional imaging modalities --> in patients with high-risk SCC, skin exceeding SCC or suspected metastases [25] [11]

Therapy

Surgical therapy

First line treatment is surgical excision with histological control

Therapeutic target is a complete excision (R0) with histological examination of the excision margins

Until R0 resection is confirmed wound closure should only take place if the excision margins can be clearly assigned postoperatively and only if primary closure without further undermining of the wound surroundings is possible to prevent scattering of tumor cells

A prophylactic lymphadenectomy should not be performed

In case of a clinically confirmed lmyphnode metastasis a regional lymphadenectomy is recommended [19]

Radiotherapy

If a complete excision is not possible or if there are contraindications for surgical treatment irradiation should be considered after discussion in an interdisciplinary tumor board

In case of R1- / R2-resection or extensive affection of lymph nodes (> 1 lymph node, lymph node metastasis > 3 cm, involvement of intraparotid lymphnodes) postoperative radiotherapy is recommended

In case of excision margin < 2 mm or perineural infiltration adjuvant radiotherapy should be performed [19]

Systemic medication

The indication for a systemic therapy should be discussed by an interdisciplinary tumorboard

In case of systemic therapy, patients should be included in clinical trials

There are no controlled or randomized studies that show the benefit of a systemic therapy in metastatic SCC [19]

Aftercare

Squamous cell carcinomas with low risk of recurrence: follow-up every 6 months for the first 2 years, then once a year for two or three more years

Squamous cell carcinomas with high risk of recurrence: follow-up every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for two or three more years, afterwards once a year [19]

Note: Squamous cell carcinomas with a stage T4, L1 or M1 at the initial diagnoses have to be reported to the German cancer registry on an obligatory basis since 1.1.2023.

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant Melanoma

Spinocelluar carcinoma

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant melanomas are the third most common type of skin cancer (they represent approximately 3 % - 5 % of skin cancer) and they are caused by malignancy of melanocytes. [1] [23]

Risk factors

Genetic predisposition: Fitzpatrick skin types I, II and III, congenital melanocytic nevi (depending on the diameter, risk starts to increase at a diameter of 20 cm), family history of melanoma

Aquired factors: history of melanoma, dysplastic nevus cell nevi, number of nevus cell nevi

External factors: UV exposition (notably intermittent and strong exposition) [26] [24]

Pathogenesis

Mutations of the genome (most common BRAF mutation) can activate signaling pathways leading to uncontrollable cell growth. Two-thirds of melanomas are de novo formations, one-third of melanomas develops out of preexisting lesions. [24]

Histological subtypes

Superficial Spreading Melanoma (SSM): SSM is the most common type of melanoma. (60 % - 70 %) Typically it is located at the torso or at the backside of the legs. Clinically it appears as sharply marginated papule or nodule and shows a variety of colors including tan, brown, gray, black, violaceus, pink and rarely white. In the beginning it has a slow horizontal growth phase.

Nodular Melanoma (NMM): NMM accounts for 20 % - 30 % of melanomas. It is more common in males than in females and often it is located at the torso, head or limbs. Clinically it has a uniform brown or black color and can present as a nodule, as an ulcerated polyp or as an elevated plaque. It has only a vertical growth phase leading to higher rate of metastasis and a worse prognosis than the other subtypes.

Lentigo Maligno Melanoma (LMM): About 10 % of melanomas are LMMs. This type of skin cancer occurs more often in older persons. Common localizations are sun-exposed areas (in particular the face). Clinically it manifests as a flat tumor with irregular outlines and shows a variety of colors. It has a low growth proceeding from a lentigo maligna.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma (ALM): AML is a rare type of skin cancer (5 % of melanomas) and is more common in Asian, Hispanic or African patients. It is mainly found on glabrous skin and adjacent skin of digits, palms and soles. It appears as brown or black plaque and can form ulcerations and knots after a while. It can also be located under the nail of the thumb or great toe clinically resulting in a longitudinal brown nail pigmentation in combination with periungual pigmentation. (= Hutchinson-sign) Typically it has a slow horizontal growth. [26]

Clinical presentation

Common characteristics: Nodules or plaques with mostly dark brown to bluish-black in color; high variation in clinical appearance and localization (see histological subtypes)

Typical Localization: high variation in clinical appearance and localization (see histological subtypes)

Special types: Amelanotic malignant melanoma, mucosal melanoma, choroid melanoma

Metastasis formation: In the beginning mainly lymphatic metastatic spread (two-thirds) leading to satellite metastases (maximal distance to the primary tumor is 2 cm) or in-transit metastases (located between primary tumor and his following lymph node), over time also hematogenous metastatic spread in particular concerning skin, liver, bones, central nervous system and lungs

Diagnostic

History: previous skin tumors, pre-existing skin lesions, family history, UV exposition, B symptoms

Clinical examination: inspection of the whole skin surface including mucosa (see common characteristics), palpation (especially local lymphatic nodes)

Instrument-based diagnostic: dermatoscopy, sequential digital dermatoscopic imaging, confocal laser scanning microscopy

Primary excisional biopsy and histopathological examination: all melanoma suspect skin lesions, with a resection margin of 2 mm --> Staging and classification of melanomas according to AJCC 2016 [20]

ABCDE-criteria

: A = Asymmetry

, B = Border irregularity

, C = Color variation

, D = Diameter > 6 mm

, E = Evolving (changes of the skin lesion within the last three months) [26]

: A = Asymmetry

, B = Border irregularity

, C = Color variation

, D = Diameter > 6 mm

, E = Evolving (changes of the skin lesion within the last three months) [26]

Breslow thickness

= Thickness of the tumor between stratum granulosum and lowermost cell of the tumor

Most important prognosis factor

Classification: Breslow level I means thickness ≤ 1 mm, Breslow level II means thickness ≤ 2 mm, Breslow level III means thickness ≤ 4 mm, Breslow level IV means thickness > 4 mm [9]

Staging diagnostic

Sonography: lymphnodes (stage Ib or higher), abdomen (stage IV)

Laboratory: S100B (stage Ib or higher), LDH (stage IIc or higher)

Radiology: full-body-CT / MRI (stage IIc or higher), MRI of the head (stage IIc or higher), skeletal scintigraphy (stage IV)

Molecular pathology: mutation of BRAF-gene (stage IIIb or higher), mutation of NRAS-gene (stage IIIb or higher), mutation of c-KIT gene (stage IIIb or higher) [20]

*Stages according to AJCC 2016

Therapy of primary tumor

Surgical therapy

A suspected melanoma should be completely excised with a scarce distance to healthy tissue (For melanomas stage pT1, pT2 a excision margin of 1 cm is recommended, for melanomas stage pT3, pT4 a excision margin of 2 cm is recommended)

Excision extending to the subcutaneous fat tissue is sufficient, there is no additional benefit from a resection of the fascia

In case of melanomas located at specific anatomical regions (e. g. face, ears, fingers) excision margins can be shortened

In case of incomplete resection (R1- / R2- Status) a further resection is recommended if a complete tumor excision (R0-status) can be achieved (If a complete R0-resection is not possible through surgical excision, other therapeutical options should be considered) [20]

In case of melanomas with a thickness > 1 mm a sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed.

Radiotherapy

In case of Lentigo maligna melanomas (carcinoma in situ) that cannot be excised due to extent or location primary radiotherapy is recommended

Incomplete excised melanomas (R1- / R2-status) with no possibility of further resection should be treated with radiotherapy

In incomplete (R1- / R2-status) or with insufficient distance to healthy tissue (< 1 cm) excised desmoplastic melanomas postoperative radiotherapy should be performed [20]

Therapy of melanomas with locoregional metastasis

Surgical therapy

Surgical therapy of locoregional metastases is recommended if there is no evidence for distant metastases and if a complete removal (R0-resection) is possible. [20]

Radiotherapy

Satellite and in-transit metastases can be treated with radiotherapy to achieve local tumor control. [20]

Drug based therapy

Patients with inoperable satellite metastases or inoperable in-transit metastases should be included in clinical trials

In case of inoperable satellite metastases or inoperable in-transit metastases various local treatments can be performed, it is supposed that intratumoral injection (Interleukin 2) and intratumoral chemotherapy (Bleomycin / Cisplatin) provide most effective tumor control [20]

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP)

In patients with multiple, rapidly recurring metastases (concerning only one arm / leg) indication for isolated limb perfusion should be reconsidered. [20]

Therapy of melanomas with distant metastases

Surgical therapy

Resection of distant metastases should be considered if R0 resection is technically possible, if it is not leading to an unacceptable loss of function and if other therapeutical options remain unrewarding. [20]

Drug based therapy

As there is not enough literature available a general recommendation for adjuvant therapy cannot be given

Available types of drugs: signal transduction inhibitors (BRAF inhibitors, MEK inhibitors, c-KIT inhibitors), checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1 antibodies), chemotherapy

In case of BRAF-V600 mutation a therapy with a BRAF inhibitor in combination with a MEK inhibitor or a checkpoint inhibitor should be implemented

In patients with unresectable metastases immunotherapy should be discussed, according to the literature PD-1 antibodies or PD-1 antibodies in combination with ipilimumab lead to the highest rate of overall survival

If immunotherapy with PD-1 antibodies is not possible in patients with unresectable metastases a polychemotherapy should be offered

Under targeted therapy with BRAF-inhibitors, MEK-inhibitors or other checkpoint inhibitors other organs may be affected by side effects

Occurrence of serious side effects (e. g. autoimmune colitis, hepatic side effects, pneumonitis) should be treated in cooperation with the respective specialties. [20]

Radiotherapy

Distant metastases in skin, subcutis or lymph nodes that cannot be excised (due to size, number or location) can be treated with radiotherapy to improve quality of life and reduce pain

Radiotherapy can happen parallel or sequentially to systemic drug-based therapy. [20]

Aftercare

Melanomas stage Ia: follow-up every 6 months for the first three years, then once per year for seven more years

Melanomas stage Ib – IIb: follow-up every 3 months for the first three years, then every six to twelfth months for seven more years

Melanomas stage IIc – IV: follow-up every 3 months for the first five years, then every six months for five more years [20]

Further (less common) malignant skin tumors are: lymphoma, Merkel cell tumor, Kaposi’s sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma

Further considerations

As malignant skin tumors may concern multiple organs the respective specialties should be involved in the therapy. To provide an optimal treatment a close cooperation especially between dermatologists and plastic surgeons is necessary.

Therefore the following standard was established at authors hospital:

Basal cell carcinoma

If a surgical resection is technically not possible patients should be presented to an interdisciplinary tumor board

After R0 resection patients with basal cell carcinoma should be treated in the dermatology outpatient clinic to provide adjusted accordingly aftercare

Patients with incomplete resection (R1 resection) should be referred to a dermatologist by way of consultation

Squamous cell carcinoma

If a surgical resection is technically not possible or metastases are suspected patients should be presented to an interdisciplinary tumor board

If a surgical resection is possible, patients with squamous cell carcinoma should be referred to a dermatologist by way of consultation after resection

Malignant melanoma

Cases of patients with malignant melanomas ≤ stage IIb should be referred to a dermatologist by way of consultation

Cases of patients with malignant melanomas ≥ stage IIb should be presented to and discussed by an interdisciplinary tumor board

Spinocelluar carcinoma

Spinocelluar carcinoma

05

Excursus: Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs micrographic surgery)

Microscopically controlled surgery is defined as a tumor excision with subsequent complete visualization of the excision margins without diagnostic gaps. [3]

Usually a conventional histological examination is used to evaluate the tumor and its excision margins. Conventional histological examination may simulate a R0 resection as not the whole tumor border is integrated in the histological processing. The fewer sections are made through the excised material, the greater the risk that tumor extensions will not found. As a conclusion histological methods that examine the complete tumor margins are significantly more sensitive. The superiority of the microscopically controlled surgery compared to conventional histology has been well documented in large comparative overviews. [3] [30]

When processing the edges of a excised tumor the aim is to represent its three-dimensional edges in two-dimensional histological sections. There are a different options of histologically processing the excised tumor, the paraffin section method and the cryostat procedure. In the context of the paraffin section method a vertical incision of the lateral tumor border is made and the tumor margin is separated as a strip. In this way the three-dimensional outer edges are brought into two-dimensionality of a histological section plane. Another option of microscopically controlled surgery is to remove the tumor in the form of a bowl and process it in the cryostat procedure. Compared to conventional histological processing, the effort of a 3D histology in the paraffin section method is not necessarily higher, whereas there is significantly more effort of a 3D histology in the cryostat process.

The sensitivity of microscopically controlled surgery to detect tumor extensions is very high. Therefore, the distance to healthy tissue during excision can be kept small, if necessary. This is conductive for good aesthetic results after reconstructive surgical procedures. However, it should be noted that with small excision margins more follow-up surgeries are necessary on average. This has to be considered in each individual case. But in total, large studies show very low recurrence rates after excision of skin tumors and examination of the excision margins with 3D histology. [3] [28] [6] [18] [7]

Cave: 3D histology can only be used in soft tissue tumors. Processing of osseous structures is only possible after decalcification. [3]

06

Surgical therapy of skin- and soft tissue lesions

Resection of malignant skin tumors may lead to extensive skin- or soft tissue lesions that cannot be closed by a primary wound suture. There are numerous methods for plastic reconstruction depending on the size and location of the tissue defect. The following chapter provides an overview of general reconstruction principles and different techniques.

General principles of reconstruction

The choice of the method for plastic reconstruction depends on many different influencing variables that may be different for each patient and defect. Wounds of the same location and same size may be treated unequally in different patients depending on varying factors. Nevertheless, there a few general principles when it comes to surgical reconstruction that should always be considered. [27]

Preoperative evaluation of the defect, especially etiology, location, extension in width and depth. Regarding the depth it is important to analyze if there are any functional structures (such as muscles, tendons, bones) are exposed. Furthermore, in terms of the location also the surrounding tissue has to be assessed in regard to skin-color, hairiness and texture. It is important to consider the specific characteristics of the respective anatomic region. In particular in the face (where malignant skin tumors are located often) it is essential to preserve functional structures for e. g. closing the eyes, closing the mouth and free nasal breathing. [27]

In terms of plastic reconstruction it is also important to pay attention to the individual characteristics of each patient, especially age, comorbidities and the patient request have to be considered. [27]

Principle of the “reconstructive ladder”: This describes the principle of escalating reconstruction procedures adapted to the tissue defect. As a general rule, the aim is to reconstruct a tissue defect using the simplest possible method that leads to the best outcome. The patient’s individual situation always has to be considered in the decision process as age and risk factors may change the decision towards a more simple or complex method. [27]

For every plastic reconstruction the principle “replace like with like” (established by Sir Harold Gillis) should be applied. This means, whenever it is possible to recreate an area with tissue similar to the surrounding tissue. [10] [27]

Furthermore, the experience and the personal preference of the surgeon should be included in the decision-making process. [27]

Selected reconstruction techniques

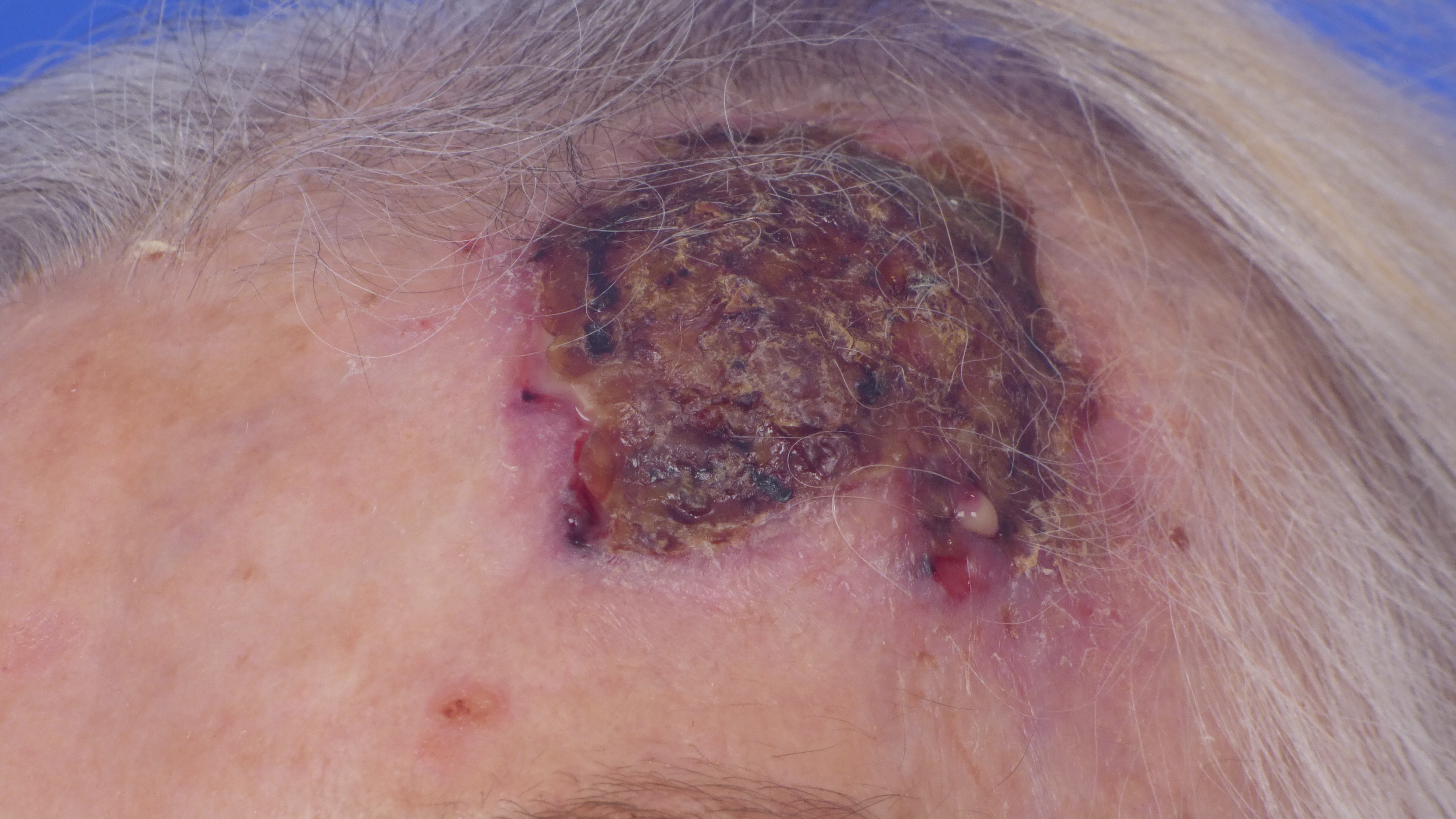

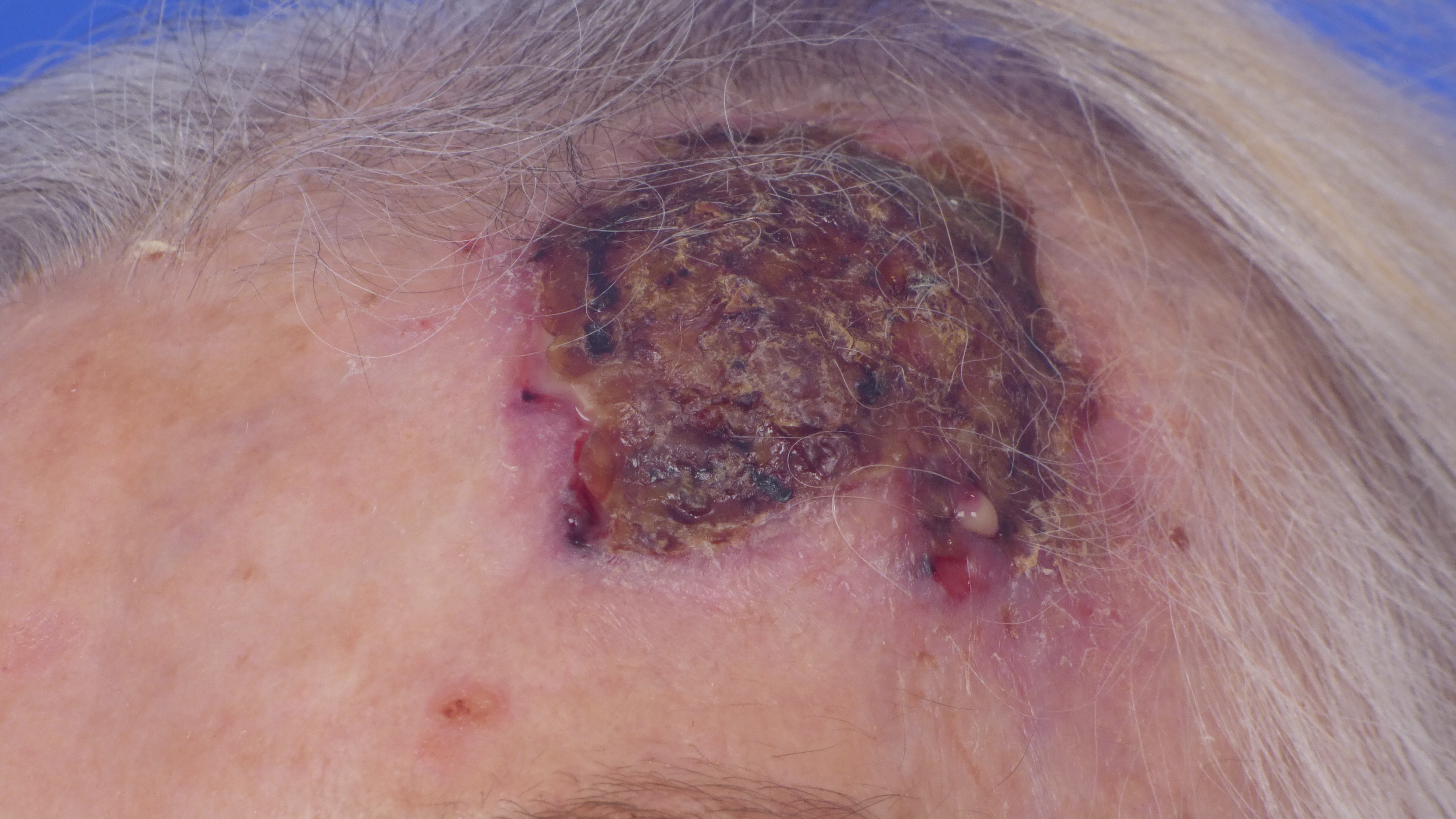

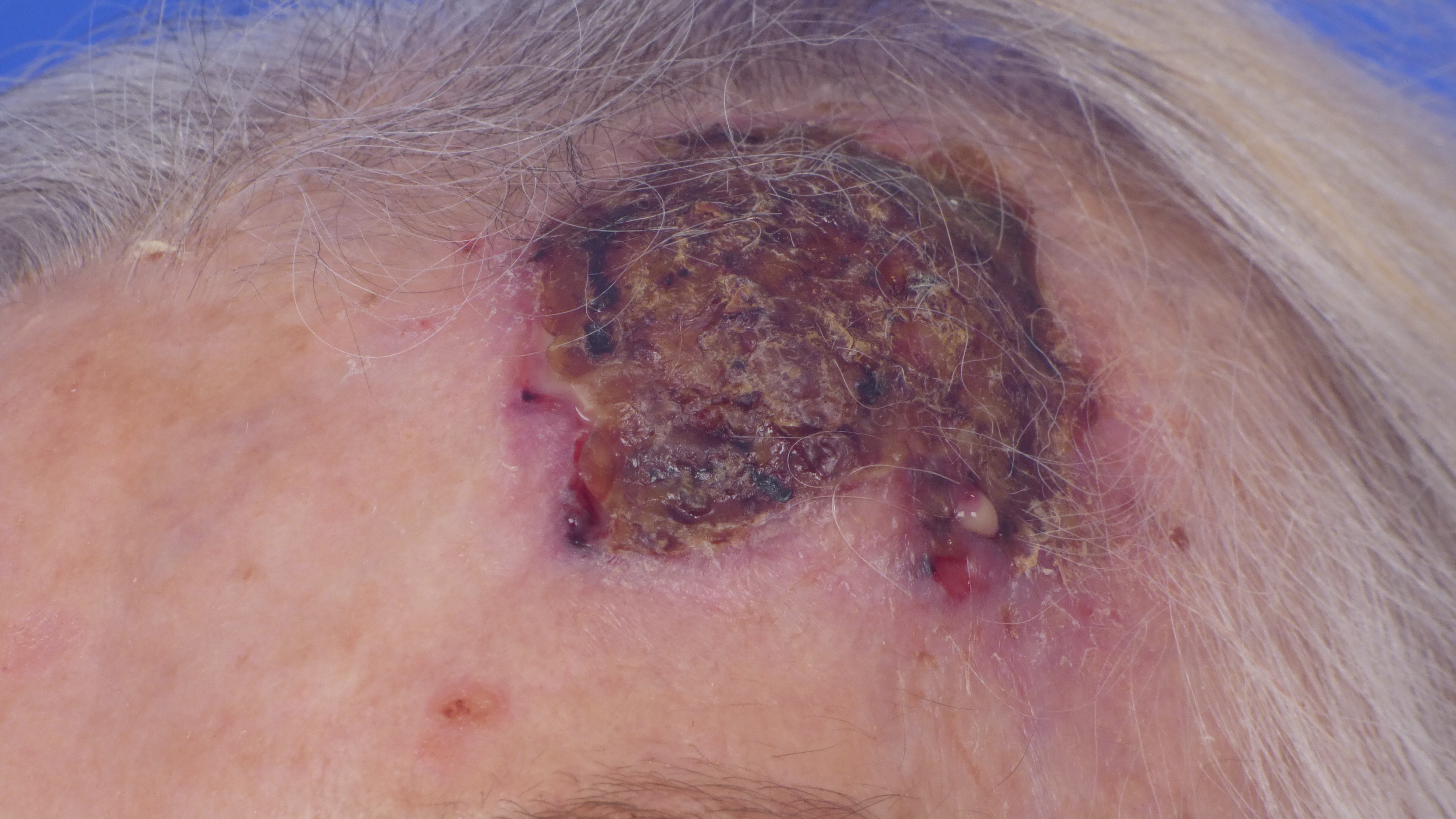

The following images show a few exemplary reconstructions of aesthetically sensitive facial areas affected by malignant skin tumors.

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Lip reconstruction - pentagonal excision, orbicularis oris muscle reconstruction, labial skin advancement

Lip reconstruction - pentagonal excision, orbicularis oris muscle reconstruction, labial skin advancement

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

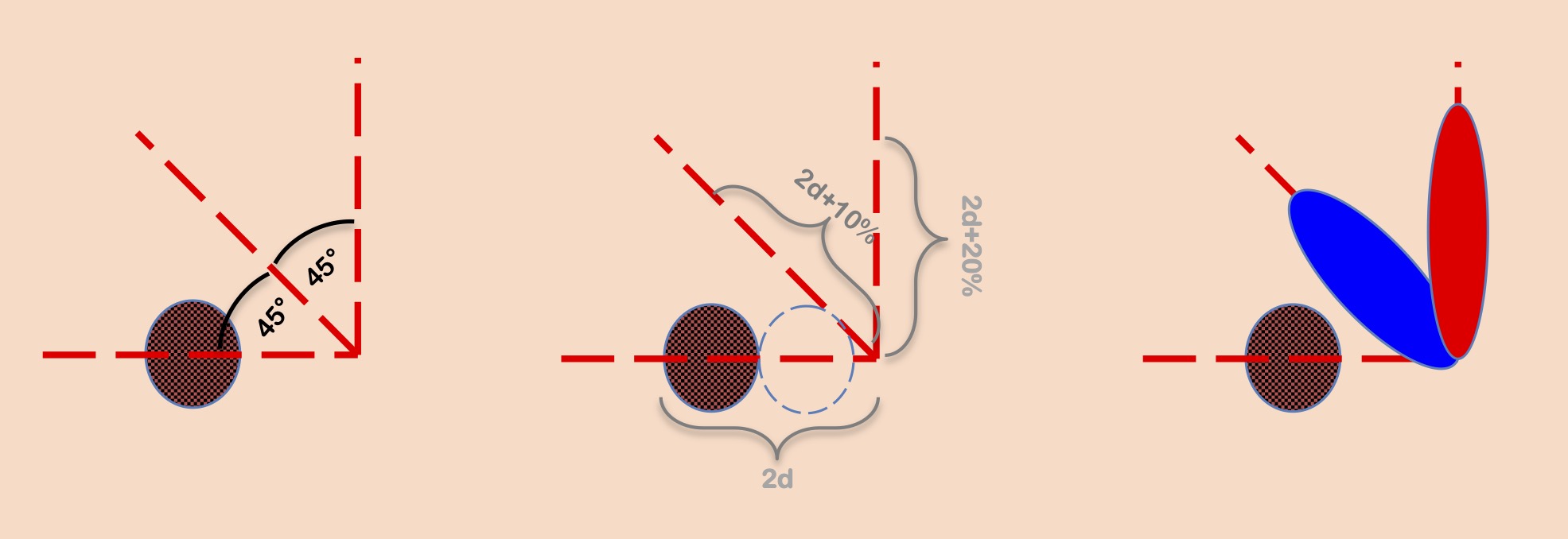

Limberg transposition flap

Dufourmentel transposition flap

Bilobed flap

07

References

1. Ahmed B., Qadir M.I., und Ghafoor S. (2020) Malignant Melanoma: Skin Cancer-Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 30: S. 291-297.

2. Bommas-Ebert U., Teubner P., und Voß R. (2006) Kurzlehrbuch Anatomie und Embryologie, 2. Auflage. Thieme.

3. Breuninger H., Konz B., und Burg G. (2007) Mikroskopisch kontrollierte Chirurgie bei malignen Hauttumoren. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 26.

4. Carmichael S.W. (2014) The tangled web of Langer's lines. Clin Anat. 27: S. 162-8.

5. Deinlein T., Richtig G., Schwab C., Scarfi F., Arzberger E., Wolf I., Hofmann-Wellenhof R., und Zalaudek I. (2016) Der Einsatz der Dermatoskopie in der Diagnose und Therapie von nichtmelanozytären Hautkrebsformen. Journal of the German Society of Dermatology.

6. Dinehart S.M., Dodge R., Stanley W.E., Franks H.H., und Pollack S.V. (1992) Basal cell carcinoma treated with Mohs surgery. A comparison of 54 younger patients with 1050 older patients. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 18: S. 560-6.

7. Eberle F.C., Schippert W., Trilling B., Rocken M., und Breuninger H. (2005) Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 3: S. 109-12.

8. Eren S., Fritz K., Salavastru C.M., und Tiplica G.S. (2022) [The most common benign cutaneous neoplasms of the epidermis and appendages and their treatment]. Hautarzt. 73: S. 94-103.

9. Ge L., Vilain R.E., Lo S., Aivazian K., Scolyer R.A., und Thompson J.F. (2016) Breslow Thickness Measurements of Melanomas Around American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Cut-Off Points: Imprecision and Terminal Digit Bias Have Important Implications for Staging and Patient Management. Ann Surg Oncol. 23: S. 2658-63.

10. Gillies H. (1920) Plastic Surgery of the Face. Hodder & Stoughton, London.

11. Heppt M.V., Leiter U., Steeb T., Amaral T., Bauer A., Becker J.C., Breitbart E., Breuninger H., Diepgen T., Dirschka T., Eigentler T., Flaig M., Follmann M., Fritz K., Greinert R., Gutzmer R., Hillen U., Ihrler S., John S.M., Kolbl O., Kraywinkel K., Loser C., Nashan D., Noor S., Nothacker M., Pfannenberg C., Salavastru C., Schmitz L., Stockfleth E., Szeimies R.M., Ulrich C., Welzel J., Wermker K., Berking C., und Garbe C. (2020) S3-Leitlinie „Aktinische Keratose und Plattenepithelkarzinom der Haut“ - Kurzfassung, Teil 1: Diagnostik, Interventionen bei aktinischen Keratosen, Versorgungsstrukturen und Qualitätsindikatoren. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18: S. 275-294.

12. Ingraffea A. (2013) Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 21: S. 21-32.

13. Kanitakis J. (2002) Anatomy, histology and immunohistochemistry of normal human skin. Eur J Dermatol. 12: S. 390-9; quiz 400-1.

14. Kelley L.C. und Hruza G.J. (2003) Benign skin tumors. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 11: S. 243-51.

15. Kim D.P., Kus K.J.B., und Ruiz E. (2019) Basal Cell Carcinoma Review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 33: S. 13-24.

16. Lang B.M., Balermpas P., Bauer A., Blum A., Brolsch G.F., Dirschka T., Follmann M., Frank J., Frerich B., Fritz K., Hauschild A., Heindl L.M., Howaldt H.P., Ihrler S., Kakkassery V., Klumpp B., Krause-Bergmann A., Loser C., Meissner M., Sachse M.M., Schlaak M., Schon M.P., Tischendorf L., Tronnier M., Vordermark D., Welzel J., Weichenthal M., Wiegand S., Kaufmann R., und Grabbe S. (2019) S2k-Leitlinie Basalzellkarzinom der Haut - Teil 1: Epidemiologie, Genetik und Diagnostik. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 17: S. 94-104.

17. Lang B.M., Balermpas P., Bauer A., Blum A., Brolsch G.F., Dirschka T., Follmann M., Frank J., Frerich B., Fritz K., Hauschild A., Heindl L.M., Howaldt H.P., Ihrler S., Kakkassery V., Klumpp B., Krause-Bergmann A., Loser C., Meissner M., Sachse M.M., Schlaak M., Schon M.P., Tischendorf L., Tronnier M., Vordermark D., Welzel J., Weichenthal M., Wiegand S., Kaufmann R., und Grabbe S. (2019) S2k Guidelines for Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma - Part 2: Treatment, Prevention and Follow-up. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 17: S. 214-230.

18. Leibovitch I., Huilgol S.C., Selva D., Hill D., Richards S., und Paver R. (2005) Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery in Australia I. Experience over 10 years. J Am Acad Dermatol. 53: S. 253-60.

19. Leiter U., Heppt M.V., Steeb T., Amaral T., Bauer A., Becker J.C., Breitbart E., Breuninger H., Diepgen T., Dirschka T., Eigentler T., Flaig M., Follmann M., Fritz K., Greinert R., Gutzmer R., Hillen U., Ihrler S., John S.M., Kolbl O., Kraywinkel K., Loser C., Nashan D., Noor S., Nothacker M., Pfannenberg C., Salavastru C., Schmitz L., Stockfleth E., Szeimies R.M., Ulrich C., Welzel J., Wermker K., Garbe C., und Berking C. (2020) S3-Leitlinie „Aktinische Keratose und Plattenepithelkarzinom der Haut“ - Kurzfassung, Teil 2: Epidemiologie, chirurgische und systemische Therapie des Plattenepithelkarzinoms, Nachsorge, Prävention und Berufskrankheit. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18: S. 400-413.

20. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft D.K. und AWMF) (2020) S3 - Leitlinie zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Melanoms. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18.

21. Luba M.C., Bangs S.A., Mohler A.M., und Stulberg D.L. (2003) Common benign skin tumors. Am Fam Physician. 67: S. 729-38.

22. Lüllmann-Rauch R. (2006) Histologie, 2. Auflage. Thieme.

23. Pavri S.N., Clune J., Ariyan S., und Narayan D. (2016) Malignant Melanoma: Beyond the Basics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 138: S. 330e-340e.

24. Pflugfelder A., Weide B., Eigentler T.K., Forschner A., Leiter U., Held L., Meier F., und Garbe C. (2010) Incisional biopsy and melanoma prognosis: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 28: S. 316-8.

25. Plewig G., Ruzicka T., Kaufmann R., und Hertl M. (2018) Braun-Falco’s Dermatologie, Venerologie und Allergologie. Vol. 7. Springer-Verlag.

26. Rastrelli M., Tropea S., Rossi C.R., und Alaibac M. (2014) Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 28: S. 1005-11.

27. Riedel F. und Hormann K. (2005) [Plastic surgery of skin defects in the face. Principles and perspectives]. HNO. 53: S. 1020-36.

28. Rigel D.S., Robins P., und Friedman R.J. (1981) Predicting recurrence of basal-cell carcinomas treated by microscopically controlled excision: a recurrence index score. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 7: S. 807-10.

29. Son D. und Harijan A. (2014) Overview of surgical scar prevention and management. J Korean Med Sci. 29: S. 751-7.

30. Thissen M.R., Neumann M.H., und Schouten L.J. (1999) A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 135: S. 1177-83.

31. Vela-Romera A., Carriel V., Martin-Piedra M.A., Aneiros-Fernandez J., Campos F., Chato-Astrain J., Prados-Olleta N., Campos A., Alaminos M., und Garzon I. (2019) Characterization of the human ridged and non-ridged skin: a comprehensive histological, histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis. Histochem Cell Biol. 151: S. 57-73.

32. Waldman A. und Schmults C. (2019) Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 33: S. 1-12.

2. Bommas-Ebert U., Teubner P., und Voß R. (2006) Kurzlehrbuch Anatomie und Embryologie, 2. Auflage. Thieme.

3. Breuninger H., Konz B., und Burg G. (2007) Mikroskopisch kontrollierte Chirurgie bei malignen Hauttumoren. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 26.

4. Carmichael S.W. (2014) The tangled web of Langer's lines. Clin Anat. 27: S. 162-8.

5. Deinlein T., Richtig G., Schwab C., Scarfi F., Arzberger E., Wolf I., Hofmann-Wellenhof R., und Zalaudek I. (2016) Der Einsatz der Dermatoskopie in der Diagnose und Therapie von nichtmelanozytären Hautkrebsformen. Journal of the German Society of Dermatology.

6. Dinehart S.M., Dodge R., Stanley W.E., Franks H.H., und Pollack S.V. (1992) Basal cell carcinoma treated with Mohs surgery. A comparison of 54 younger patients with 1050 older patients. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 18: S. 560-6.

7. Eberle F.C., Schippert W., Trilling B., Rocken M., und Breuninger H. (2005) Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 3: S. 109-12.

8. Eren S., Fritz K., Salavastru C.M., und Tiplica G.S. (2022) [The most common benign cutaneous neoplasms of the epidermis and appendages and their treatment]. Hautarzt. 73: S. 94-103.

9. Ge L., Vilain R.E., Lo S., Aivazian K., Scolyer R.A., und Thompson J.F. (2016) Breslow Thickness Measurements of Melanomas Around American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Cut-Off Points: Imprecision and Terminal Digit Bias Have Important Implications for Staging and Patient Management. Ann Surg Oncol. 23: S. 2658-63.

10. Gillies H. (1920) Plastic Surgery of the Face. Hodder & Stoughton, London.

11. Heppt M.V., Leiter U., Steeb T., Amaral T., Bauer A., Becker J.C., Breitbart E., Breuninger H., Diepgen T., Dirschka T., Eigentler T., Flaig M., Follmann M., Fritz K., Greinert R., Gutzmer R., Hillen U., Ihrler S., John S.M., Kolbl O., Kraywinkel K., Loser C., Nashan D., Noor S., Nothacker M., Pfannenberg C., Salavastru C., Schmitz L., Stockfleth E., Szeimies R.M., Ulrich C., Welzel J., Wermker K., Berking C., und Garbe C. (2020) S3-Leitlinie „Aktinische Keratose und Plattenepithelkarzinom der Haut“ - Kurzfassung, Teil 1: Diagnostik, Interventionen bei aktinischen Keratosen, Versorgungsstrukturen und Qualitätsindikatoren. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18: S. 275-294.

12. Ingraffea A. (2013) Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 21: S. 21-32.

13. Kanitakis J. (2002) Anatomy, histology and immunohistochemistry of normal human skin. Eur J Dermatol. 12: S. 390-9; quiz 400-1.

14. Kelley L.C. und Hruza G.J. (2003) Benign skin tumors. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 11: S. 243-51.

15. Kim D.P., Kus K.J.B., und Ruiz E. (2019) Basal Cell Carcinoma Review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 33: S. 13-24.

16. Lang B.M., Balermpas P., Bauer A., Blum A., Brolsch G.F., Dirschka T., Follmann M., Frank J., Frerich B., Fritz K., Hauschild A., Heindl L.M., Howaldt H.P., Ihrler S., Kakkassery V., Klumpp B., Krause-Bergmann A., Loser C., Meissner M., Sachse M.M., Schlaak M., Schon M.P., Tischendorf L., Tronnier M., Vordermark D., Welzel J., Weichenthal M., Wiegand S., Kaufmann R., und Grabbe S. (2019) S2k-Leitlinie Basalzellkarzinom der Haut - Teil 1: Epidemiologie, Genetik und Diagnostik. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 17: S. 94-104.

17. Lang B.M., Balermpas P., Bauer A., Blum A., Brolsch G.F., Dirschka T., Follmann M., Frank J., Frerich B., Fritz K., Hauschild A., Heindl L.M., Howaldt H.P., Ihrler S., Kakkassery V., Klumpp B., Krause-Bergmann A., Loser C., Meissner M., Sachse M.M., Schlaak M., Schon M.P., Tischendorf L., Tronnier M., Vordermark D., Welzel J., Weichenthal M., Wiegand S., Kaufmann R., und Grabbe S. (2019) S2k Guidelines for Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma - Part 2: Treatment, Prevention and Follow-up. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 17: S. 214-230.

18. Leibovitch I., Huilgol S.C., Selva D., Hill D., Richards S., und Paver R. (2005) Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery in Australia I. Experience over 10 years. J Am Acad Dermatol. 53: S. 253-60.

19. Leiter U., Heppt M.V., Steeb T., Amaral T., Bauer A., Becker J.C., Breitbart E., Breuninger H., Diepgen T., Dirschka T., Eigentler T., Flaig M., Follmann M., Fritz K., Greinert R., Gutzmer R., Hillen U., Ihrler S., John S.M., Kolbl O., Kraywinkel K., Loser C., Nashan D., Noor S., Nothacker M., Pfannenberg C., Salavastru C., Schmitz L., Stockfleth E., Szeimies R.M., Ulrich C., Welzel J., Wermker K., Garbe C., und Berking C. (2020) S3-Leitlinie „Aktinische Keratose und Plattenepithelkarzinom der Haut“ - Kurzfassung, Teil 2: Epidemiologie, chirurgische und systemische Therapie des Plattenepithelkarzinoms, Nachsorge, Prävention und Berufskrankheit. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18: S. 400-413.

20. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft D.K. und AWMF) (2020) S3 - Leitlinie zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Melanoms. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 18.

21. Luba M.C., Bangs S.A., Mohler A.M., und Stulberg D.L. (2003) Common benign skin tumors. Am Fam Physician. 67: S. 729-38.

22. Lüllmann-Rauch R. (2006) Histologie, 2. Auflage. Thieme.

23. Pavri S.N., Clune J., Ariyan S., und Narayan D. (2016) Malignant Melanoma: Beyond the Basics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 138: S. 330e-340e.

24. Pflugfelder A., Weide B., Eigentler T.K., Forschner A., Leiter U., Held L., Meier F., und Garbe C. (2010) Incisional biopsy and melanoma prognosis: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 28: S. 316-8.

25. Plewig G., Ruzicka T., Kaufmann R., und Hertl M. (2018) Braun-Falco’s Dermatologie, Venerologie und Allergologie. Vol. 7. Springer-Verlag.

26. Rastrelli M., Tropea S., Rossi C.R., und Alaibac M. (2014) Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 28: S. 1005-11.

27. Riedel F. und Hormann K. (2005) [Plastic surgery of skin defects in the face. Principles and perspectives]. HNO. 53: S. 1020-36.

28. Rigel D.S., Robins P., und Friedman R.J. (1981) Predicting recurrence of basal-cell carcinomas treated by microscopically controlled excision: a recurrence index score. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 7: S. 807-10.

29. Son D. und Harijan A. (2014) Overview of surgical scar prevention and management. J Korean Med Sci. 29: S. 751-7.

30. Thissen M.R., Neumann M.H., und Schouten L.J. (1999) A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 135: S. 1177-83.

31. Vela-Romera A., Carriel V., Martin-Piedra M.A., Aneiros-Fernandez J., Campos F., Chato-Astrain J., Prados-Olleta N., Campos A., Alaminos M., und Garzon I. (2019) Characterization of the human ridged and non-ridged skin: a comprehensive histological, histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis. Histochem Cell Biol. 151: S. 57-73.

32. Waldman A. und Schmults C. (2019) Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 33: S. 1-12.

Images

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Ear reconstruction - preauricular pull through random pattern flap

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Eyelid reconstruction - tarso-conjunctival grafting w nasal septum and nasal mucoperichondrium, local skin advancement

Lip reconstruction - pentagonal excision, orbicularis oris muscle reconstruction, labial skin advancement

Lip reconstruction - pentagonal excision, orbicularis oris muscle reconstruction, labial skin advancement

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - dorsal nasal flap (dorsal nasal artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

Nasal reconstruction - nasolabial flap (angular artery)

Limberg transposition flap

Dufourmentel transposition flap

Bilobed flap

Spinocelluar carcinoma

Videos

References

[1]

, , ,